“Bond … JAMES Bond.”

In May 1960, an American U-2 spy plane was shot down by the Russians over Soviet territory, which caused something of a crisis in the free world at that time. Francis Gary Powers (the pilot) bailed out of the plane safely, but was quickly captured by the Russians, and forced to admit that he was a spy for the CIA (which he really was). The Soviets had all that was left of the crashed aircraft, along with the spying technology that had survived the crash. They also had actual photos of the Russian military bases that the cameras from on board the plane had taken. After denying the military nature of the plane's mission, the United States eventually admitted that the aircraft was a spy plane; and not out on a “weather research mission” as it had originally claimed.

American pilot Francis Gary Powers, in a special pressure suit for stratospheric flying

What happened to the pilot of the U-2 spy plane shot down in 1960?

Unfortunately for Mr. Powers, the Soviets actually convicted him of espionage three months later. They thus sentenced him to a full three years' imprisonment and seven years' hard labor. Fortunately for Powers, though, his country had already captured Soviet agent Rudolf Abel for a like offense; and exchanged him for both Powers and an American student named Frederic Pryor in 1962. Powers was thus able to go home as a free man at that time, and thus got off relatively easily – after only serving two years of his sentence from the Soviets. But many other spies were not so lucky, and some were killed when the Russians discovered them. The Americans, too, engaged in some executions of convicted spies, of course; as did most other countries that participated in the Cold War. But the Soviet executions had a particular reputation for brutality (and wanton cruelty), and they could get away with sentencing more people because of their standards of evidence being somewhat lower than in the free world. Being a spy was not a “glamorous thing” like in the movies for most agents, it would seem. Thus, the casualties of the Cold War were not limited to actual “shooting wars” between the two sides.

American pilot Francis Gary Powers, when he was in Soviet custody

Western attitudes towards spying were, for a time, influenced by the “Red Scare” of the 1950's

In the earliest portion of the Cold War, attitudes towards spying in the United States (and some other Western nations) were affected by the “Red Scare” of the 1950's. This era is rightfully identified with some hysterical fears about communist infiltration; and a certain amount of “witch-hunting” against suspected communists, both real and otherwise. The term “communist” was so deeply unpopular at this time, in fact, that it would be like calling someone a “racist” in the United States today. People like Joseph McCarthy capitalized on these fears to great effect to smear their political enemies, and so the era is today identified with the word “McCarthyism” in the United States. There were clearly many false accusations against people who had never been communists. There were also many persecutions of people who really were communists, but who had never been disloyal to their native countries as they were then alleged to be. (They would have seen the “Marxism-Leninism” policies of the Eastern Bloc as something of a betrayal of “true communism,” as they saw it, and had no sympathy with the “Russian enemy” as they were then claimed to have.) Nonetheless, the thing that has sometimes gotten lost here is that there really was a communist infiltration in the Western nations (even if it was overblown); and that there really was a kernel of truth in some of the allegations against the communist sympathizers – including Alger Hiss, one of the most defended of them. McCarthy has been so thoroughly discredited today (and rightfully so) that socialists and communists today often try to identify their opponents with him, almost as though any opposition to Marxism were equivalent to McCarthyism. The pendulum seems to have swung too far in the opposite direction, I think. Thus, the truth about Cold War spying (and a few other things) would seem to be ignored sometimes for this reason.

In the earliest portion of the Cold War, attitudes towards spying in the United States (and some other Western nations) were affected by the “Red Scare” of the 1950's. This era is rightfully identified with some hysterical fears about communist infiltration; and a certain amount of “witch-hunting” against suspected communists, both real and otherwise. The term “communist” was so deeply unpopular at this time, in fact, that it would be like calling someone a “racist” in the United States today. People like Joseph McCarthy capitalized on these fears to great effect to smear their political enemies, and so the era is today identified with the word “McCarthyism” in the United States. There were clearly many false accusations against people who had never been communists. There were also many persecutions of people who really were communists, but who had never been disloyal to their native countries as they were then alleged to be. (They would have seen the “Marxism-Leninism” policies of the Eastern Bloc as something of a betrayal of “true communism,” as they saw it, and had no sympathy with the “Russian enemy” as they were then claimed to have.) Nonetheless, the thing that has sometimes gotten lost here is that there really was a communist infiltration in the Western nations (even if it was overblown); and that there really was a kernel of truth in some of the allegations against the communist sympathizers – including Alger Hiss, one of the most defended of them. McCarthy has been so thoroughly discredited today (and rightfully so) that socialists and communists today often try to identify their opponents with him, almost as though any opposition to Marxism were equivalent to McCarthyism. The pendulum seems to have swung too far in the opposite direction, I think. Thus, the truth about Cold War spying (and a few other things) would seem to be ignored sometimes for this reason.

American Senator Joseph McCarthy

Among other things, secret agents sometimes obtained information about nuclear weapons

Some of the most controversial events of the “Red Scare” period, in fact, were the American executions of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg in the electric chair. At the time I write this, they are the only American civilians ever to be executed in peacetime for treason. Specifically, the American government alleged that they had passed nuclear secrets to the Russians, but some have questioned whether they really did so. Since that time, the Russians have declassified some of their records on this subject, which reveal that the Rosenbergs were involved in passing these nuclear secrets. Thus, the controversy over their guilt has largely died down; although the matter of the trial is still somewhat controversial. Some argue, in fact, that the prosecutors falsified (at least some of) their evidence. They believe that the “real evidence” was not used because it had been obtained secretly from breaking the Soviet codes, and the government “didn't want the Russians to find out” how much they really knew about these codes – which would have inevitably come out, if this evidence had been used at trial. This is an area of controversy, and I will not attempt to settle it here. But most would agree today that the Rosenbergs were really guilty, at least, and that nuclear weapons secrets were very coveted information at this time (and still are today). Both sides spent vast sums of money trying to get it, of course, and sometimes even succeeded in doing so. They wanted to know how the weapons were built, how to make them, how advanced they were, and where they were located; and this information all came at a price. Sometimes, this price was in human life; and both sides paid much for spying on the other.

Some of the most controversial events of the “Red Scare” period, in fact, were the American executions of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg in the electric chair. At the time I write this, they are the only American civilians ever to be executed in peacetime for treason. Specifically, the American government alleged that they had passed nuclear secrets to the Russians, but some have questioned whether they really did so. Since that time, the Russians have declassified some of their records on this subject, which reveal that the Rosenbergs were involved in passing these nuclear secrets. Thus, the controversy over their guilt has largely died down; although the matter of the trial is still somewhat controversial. Some argue, in fact, that the prosecutors falsified (at least some of) their evidence. They believe that the “real evidence” was not used because it had been obtained secretly from breaking the Soviet codes, and the government “didn't want the Russians to find out” how much they really knew about these codes – which would have inevitably come out, if this evidence had been used at trial. This is an area of controversy, and I will not attempt to settle it here. But most would agree today that the Rosenbergs were really guilty, at least, and that nuclear weapons secrets were very coveted information at this time (and still are today). Both sides spent vast sums of money trying to get it, of course, and sometimes even succeeded in doing so. They wanted to know how the weapons were built, how to make them, how advanced they were, and where they were located; and this information all came at a price. Sometimes, this price was in human life; and both sides paid much for spying on the other.

Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, who really did pass information to the KGB

Both sides wanted to know the names of enemy agents, and employed “double agents”

Both sides thus placed a high premium on catching enemy spies, and were willing to pay much for accurate information about their identities. The most damaging cases of spying were often “double agents,” or people who purported to work for the one side's spy agencies, when they were actually working for the other side. When they were willing to reveal the names of the people they were ostensibly working for, the people whose identities were compromised sometimes died as a result. The Russians were particularly successful at turning some American and British officials to their cause in this struggle, with the result that many agents working behind the Iron Curtain were compromised and destroyed. Among the British officials who gave names to the KGB were Kim Philby and George Blake, and among the American officials who gave names to the KGB were Robert Hanssen and Aldrich Ames. Some of those that they had betrayed were lucky enough to be exchanged as prisoners; but once the KGB suspected someone, they were usually as good as dead. That being said, we did have some valuable Russian sources from behind the Iron Curtain itself; such as Oleg Gordievsky, Adolf Tolkachev, and Dmitri Polyakov. All three of these men were eventually betrayed by double agent Aldrich Ames, I might add here, but one survived because of British Intelligence successfully helping him to escape (namely, Oleg Gordievsky). The other two did not; and we owe them much for their sacrifice.

Both sides thus placed a high premium on catching enemy spies, and were willing to pay much for accurate information about their identities. The most damaging cases of spying were often “double agents,” or people who purported to work for the one side's spy agencies, when they were actually working for the other side. When they were willing to reveal the names of the people they were ostensibly working for, the people whose identities were compromised sometimes died as a result. The Russians were particularly successful at turning some American and British officials to their cause in this struggle, with the result that many agents working behind the Iron Curtain were compromised and destroyed. Among the British officials who gave names to the KGB were Kim Philby and George Blake, and among the American officials who gave names to the KGB were Robert Hanssen and Aldrich Ames. Some of those that they had betrayed were lucky enough to be exchanged as prisoners; but once the KGB suspected someone, they were usually as good as dead. That being said, we did have some valuable Russian sources from behind the Iron Curtain itself; such as Oleg Gordievsky, Adolf Tolkachev, and Dmitri Polyakov. All three of these men were eventually betrayed by double agent Aldrich Ames, I might add here, but one survived because of British Intelligence successfully helping him to escape (namely, Oleg Gordievsky). The other two did not; and we owe them much for their sacrifice.

Aldrich Ames, an American CIA officer who was really working for the KGB as a double agent

From the glamor of “James Bond” to the grimness of the reality

The Cold War spying captured the public imagination at this time, of course, and nowhere is this fascination better expressed than in the iconic media of this time. Most famously, the “James Bond” film series depicted the glamorous life of its title character as he spied on the enemy in exciting service to his country. Although “James Bond” was a British character, he was popular in other countries as well – including the United States (my home country), where he was well-known. The media obviously got a few things wrong here, and Hollywood always has a tendency to embellish things a little (when they get them right at all). Nonetheless, the “James Bond” film series did get a few things right about this era's spy confrontations; and it did accurately depict the communists as the “bad guys” in this struggle (which some media since the Cold War have been reluctant to do). All that being said, the spy confrontation was a war (and a brutal one at that); and as noted previously, it had a tendency to produce casualties at times. This may have been part of the reason that it was so controversial at the time, and why the Americans had such a negative view of their own Central Intelligence Agency at times. (Or for the British, the “Secret Intelligence Service” – or “MI6,” short for Military Intelligence, Section 6; the group that James Bond was often supposed to be working for in the series.) The “James Bond” film series does offer some invaluable insight into the Cold War, because its popularity tells you much about the political culture of the time. Nonetheless, the reality of the situation was somewhat grimmer; and so the spy conflict continues to be controversial today.

The Cold War spying captured the public imagination at this time, of course, and nowhere is this fascination better expressed than in the iconic media of this time. Most famously, the “James Bond” film series depicted the glamorous life of its title character as he spied on the enemy in exciting service to his country. Although “James Bond” was a British character, he was popular in other countries as well – including the United States (my home country), where he was well-known. The media obviously got a few things wrong here, and Hollywood always has a tendency to embellish things a little (when they get them right at all). Nonetheless, the “James Bond” film series did get a few things right about this era's spy confrontations; and it did accurately depict the communists as the “bad guys” in this struggle (which some media since the Cold War have been reluctant to do). All that being said, the spy confrontation was a war (and a brutal one at that); and as noted previously, it had a tendency to produce casualties at times. This may have been part of the reason that it was so controversial at the time, and why the Americans had such a negative view of their own Central Intelligence Agency at times. (Or for the British, the “Secret Intelligence Service” – or “MI6,” short for Military Intelligence, Section 6; the group that James Bond was often supposed to be working for in the series.) The “James Bond” film series does offer some invaluable insight into the Cold War, because its popularity tells you much about the political culture of the time. Nonetheless, the reality of the situation was somewhat grimmer; and so the spy conflict continues to be controversial today.

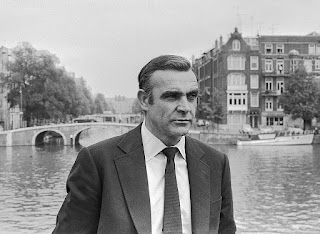

Sean Connery as “James Bond”

Secrecy can be a bit of a barrier to historians, but some of the files have been declassified

Another reason that spying is controversial is the need for (at least some amount of) secrecy, because the public sometimes has to be kept in the dark (and even lied to) about military secrets. This lack of public information has a strong tendency to encourage conspiracy theories; and so conspiracy theories abounded about the CIA (and still persist today). Moreover, it's not always easy to reconstruct the details of your typical spy war, because the very nature of the beast is to keep things secret – something which also “keeps things secret” from historians and the general public. But some things have been pieced together from the highly publicized leaks of this time, and the various governments have now declassified some of the records from that time to boot. (Including the Julius and Ethel Rosenberg records that I mentioned earlier.) Even the older Soviet records are sometimes available to the general public now, and so a two-sided view of the war is now possible for some of these things, which would never have been available at the time that it was still going on.

Another reason that spying is controversial is the need for (at least some amount of) secrecy, because the public sometimes has to be kept in the dark (and even lied to) about military secrets. This lack of public information has a strong tendency to encourage conspiracy theories; and so conspiracy theories abounded about the CIA (and still persist today). Moreover, it's not always easy to reconstruct the details of your typical spy war, because the very nature of the beast is to keep things secret – something which also “keeps things secret” from historians and the general public. But some things have been pieced together from the highly publicized leaks of this time, and the various governments have now declassified some of the records from that time to boot. (Including the Julius and Ethel Rosenberg records that I mentioned earlier.) Even the older Soviet records are sometimes available to the general public now, and so a two-sided view of the war is now possible for some of these things, which would never have been available at the time that it was still going on.

CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia

Spy planes were also used extensively – and in the later Cold War, so were spy satellites

I began this post by discussing a spy plane incident, when an American U-2 plane was shot down with the pilot captured. This capture caused some embarrassment for the American authorities, as you might imagine; because he had admitted for the cameras that his purpose was to spy on them – something that he had earlier been ordered to do, in the event that he was captured. (These orders were given to him before the mission had even started, so he was acting on orders from higher up when he made these confessions.) Having a two-year delay before he returned home was also undesirable for the family, so a better solution than spy planes was sought – and eventually obtained. The solution was spy satellites, which became possible once the technology allowed them to be sent into space to begin with. In the early years, spy satellites were not able to send information home unless they ejected canisters of photographic film that would descend to earth via parachutes. Moreover, the retrieval of these canisters was both inconvenient and somewhat dangerous. When satellites were later able to send information back to the Earth without ejecting the canisters, these complicated political risks were largely eliminated; so it was fortunate that they were able to do this at this time.

I began this post by discussing a spy plane incident, when an American U-2 plane was shot down with the pilot captured. This capture caused some embarrassment for the American authorities, as you might imagine; because he had admitted for the cameras that his purpose was to spy on them – something that he had earlier been ordered to do, in the event that he was captured. (These orders were given to him before the mission had even started, so he was acting on orders from higher up when he made these confessions.) Having a two-year delay before he returned home was also undesirable for the family, so a better solution than spy planes was sought – and eventually obtained. The solution was spy satellites, which became possible once the technology allowed them to be sent into space to begin with. In the early years, spy satellites were not able to send information home unless they ejected canisters of photographic film that would descend to earth via parachutes. Moreover, the retrieval of these canisters was both inconvenient and somewhat dangerous. When satellites were later able to send information back to the Earth without ejecting the canisters, these complicated political risks were largely eliminated; so it was fortunate that they were able to do this at this time.

American satellite image of the Pentagon, 1967 (from the Corona satellite series)

After the invention of computers, hacking also began to be used

And one other technology might also be worthy of note here, which is computers – and specifically, computer hacking. In the early part of the Cold War, this technology didn't exist, of course (or at least wasn't very sophisticated); and so neither side was able to spy on the other electronically. But once top-secret information began to be stored in computer systems, this “espionage war” began to be fought on a new front; and so this world of spying was somewhat different from any previous one. The cyberspace front continues to be relevant today, of course. The dangers and rewards of hacking continue to attract many to the subject. There is both a need to protect our country against foreign hacking, and to use our own hacking capabilities to spy on our enemies. Thus, the subject of cyberwarfare will continue to be relevant as long as we have computers; and it will not go away anytime soon.

And one other technology might also be worthy of note here, which is computers – and specifically, computer hacking. In the early part of the Cold War, this technology didn't exist, of course (or at least wasn't very sophisticated); and so neither side was able to spy on the other electronically. But once top-secret information began to be stored in computer systems, this “espionage war” began to be fought on a new front; and so this world of spying was somewhat different from any previous one. The cyberspace front continues to be relevant today, of course. The dangers and rewards of hacking continue to attract many to the subject. There is both a need to protect our country against foreign hacking, and to use our own hacking capabilities to spy on our enemies. Thus, the subject of cyberwarfare will continue to be relevant as long as we have computers; and it will not go away anytime soon.

Commodore 64 computer, first released in 1982 (one of the best-selling computers in history)

Some things about the Cold War were new, but others were timeless

Despite all this, spying has been around for a long time; and the Cold War does have some remarkable similarities to previous spy conflicts, in (at least) some ways. There were also some things about the Cold War that were new, of course, and the role of spying has become somewhat prominent in ways not previously seen. But as the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes once put it in 1651, "persons of sovereign authority [or in this case, nations] ... [are] in the state and posture of gladiators; having their weapons pointing, and their eyes fixed on one another; that is, their forts, garrisons, and guns upon the frontiers of their [nations]; and continual spies on their neighbors; which is a posture of war." (Source: "Leviathan," Chapter XIII, the subsection entitled "The incommodities of such a war") Thus, in many important ways, Thomas Hobbes' seventeenth-century quotation would seem to be a timeless description of this twentieth-century conflict; and the part about “continual spies on their neighbors” has some particular relevance for the entire Cold War period.

Despite all this, spying has been around for a long time; and the Cold War does have some remarkable similarities to previous spy conflicts, in (at least) some ways. There were also some things about the Cold War that were new, of course, and the role of spying has become somewhat prominent in ways not previously seen. But as the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes once put it in 1651, "persons of sovereign authority [or in this case, nations] ... [are] in the state and posture of gladiators; having their weapons pointing, and their eyes fixed on one another; that is, their forts, garrisons, and guns upon the frontiers of their [nations]; and continual spies on their neighbors; which is a posture of war." (Source: "Leviathan," Chapter XIII, the subsection entitled "The incommodities of such a war") Thus, in many important ways, Thomas Hobbes' seventeenth-century quotation would seem to be a timeless description of this twentieth-century conflict; and the part about “continual spies on their neighbors” has some particular relevance for the entire Cold War period.

“Therefore no one in the armed forces is treated as familiarly as are spies, no one is given rewards as rich as those given to spies, and no matter is more secret than espionage.”

– Sun Tzu's "The Art of War" (5th century BC China), Chapter 13 (as translated by Thomas Cleary)

Related movies:

Steven Spielberg's "Bridge of Spies" (2015), about the aforementioned spy plane incident

"Breach" (2007), with Chris Cooper as the aforementioned double agent Robert Hanssen

If you liked this post, you might also like:

USA spies: From the American Revolution to the Civil War

Top secret: The role of spying and code-cracking in the World Wars

A review of CNN's “The Cold War”

How did the Cold War lead to the Space Race?

Bedtime stories about Armageddon: The lessons of the Cold War about nuclear weapons

Behind the Iron Curtain: Occupation by the Soviet Union

China under Mao: The early years of Chinese communism

Berlin Blockade 1948-1949

Marshall Plan 1948-1951

Korean War 1950-1953

McCarthyism 1947-1956 (see “Espionage” post)

Cuban Revolution 1953-1959

Bay of Pigs 1961

Building of the Berlin Wall 1961-1962 (see “Eastern Europe” post)

Cuban Missile Crisis 1962

Nixon’s visit to China 1972

Vietnam War 1955-1975

Angolan Civil War 1975-2002

Soviet war in Afghanistan 1979-1989

“Able Archer 83” 1983

Reagan’s “Star Wars” program 1983-1993

Fall of the Berlin Wall 1989 (see “Star Wars” post)

Dissolution of the Soviet Union 1990-1991 (see “Star Wars” post)

Latin America in the Cold War

If you liked this post, you might also like:

USA spies: From the American Revolution to the Civil War

Top secret: The role of spying and code-cracking in the World Wars

A review of CNN's “The Cold War”

How did the Cold War lead to the Space Race?

Bedtime stories about Armageddon: The lessons of the Cold War about nuclear weapons

Behind the Iron Curtain: Occupation by the Soviet Union

China under Mao: The early years of Chinese communism

Part of a series about

The Cold War

Berlin Blockade 1948-1949

Marshall Plan 1948-1951

Korean War 1950-1953

McCarthyism 1947-1956 (see “Espionage” post)

Cuban Revolution 1953-1959

Bay of Pigs 1961

Building of the Berlin Wall 1961-1962 (see “Eastern Europe” post)

Cuban Missile Crisis 1962

Nixon’s visit to China 1972

Vietnam War 1955-1975

Angolan Civil War 1975-2002

Soviet war in Afghanistan 1979-1989

“Able Archer 83” 1983

Reagan’s “Star Wars” program 1983-1993

Fall of the Berlin Wall 1989 (see “Star Wars” post)

Dissolution of the Soviet Union 1990-1991 (see “Star Wars” post)

Latin America in the Cold War

No comments:

Post a Comment