Tuesday, December 25, 2018

A review of “Ancient Roads from Christ to Constantine”

“And the disciples were called Christians first in Antioch.”

- The New Testament, “The Acts of the Apostles,” Chapter 11, Verse 26 (as translated by the King James Version of the Bible)

Constantine was the first Roman emperor to become a Christian. Thus, “Ancient Roads from Christ to Constantine” is really a history of the early Christian faith, from its beginning with Christ to its flourishing under Constantine. After his conversion, Christianity became the dominant religion of the Roman Empire. Today, it is the world's largest religion; and it is doubtful that it would have ever become that way otherwise.

Sunday, December 16, 2018

The Habeas Corpus Act and the English Bill of Rights influenced our Constitution

“The privilege of the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in cases of rebellion or invasion the public safety may require it.”

– Article 1, Section 9, Paragraph 2 of the United States Constitution

It might come as a surprise to say this, but the British have a real “Constitution,” even if it isn't all written down in one document like ours might seem to be. Rather, it would seem to be a constitution built out of multiple documents, such as the Magna Carta and the Petition of Right (both of which I have covered in prior posts). No less important are the Habeas Corpus Act and the English Bill of Rights, which were foundational for the rights of English-speaking countries. Like the other documents mentioned here, they would both have an enormous influence on the United States Constitution. I have covered the other documents mentioned here in some other posts of this series, so I will instead focus my attention here on the Habeas Corpus Act and the English Bill of Rights (both vitally important).

Parliament of England

Actually, William Blackstone DID mention the 1689 Bill of Rights (sorry Wikipedia)

Note: There is a difference between the old and new styles of calendar, which will become relevant to our discussion.

Some Wikipedia articles are reliable, while others are not (and others are somewhere in between)

So I've often enjoyed reading articles from Wikipedia, and have linked to a number of these articles from my own blog over the years. Some of these articles are reliable, while others are not. Many of them are somewhere in between. Possibly one of these articles to be somewhere in between is the article about William Blackstone, which contained some good information about William Blackstone, and some bad information. For example, the "Criticism" section of that page said that “English jurist Jeremy Bentham was a critic of Blackstone's theories.[132] Others saw Blackstone's theories as inaccurate statements of English law, using the Constitutions of Clarendon, the Tractatus of Glanville and the 1689 Bill of Rights as particularly obvious examples of laws Blackstone omitted.” (Source: "William Blackstone" page, "Criticism" section)

Jeremy Bentham

According to Wikipedia, some have claimed that Blackstone “omitted” the 1689 Bill of Rights

The part about how “English jurist Jeremy Bentham was a critic of Blackstone's theories” is properly sourced at the “[132]”. While I don't agree with Bentham's criticisms (indeed, I find them wildly inaccurate), I do agree that he was “a critic of Blackstone's theories” – this much is pretty well-established, and that is all that the source claims here. But the second sentence has no source, which makes me wonder who exactly is making these criticisms. The sentence in question says that “Others saw Blackstone's theories as inaccurate statements of English law, using the Constitutions of Clarendon, the Tractatus of Glanville and the 1689 Bill of Rights as particularly obvious examples of laws Blackstone omitted.” Blackstone did mention both the “Constitutions of Clarendon” and the “Tractatus of Glanville” in his magnum opus, the "Commentaries on the Laws of England" (as I show in another blog post). And most relevantly, he also mentioned the “1689 Bill of Rights,” which these critics would know if they had bothered to read the very first chapter of the very first book of the “Commentaries.”

Jeremy Bentham

Monday, December 10, 2018

How did the Massachusetts Body of Liberties influence the Bill of Rights?

“No man shall be put to death without the testimony of two or three witnesses or that which is equivalent thereunto.”

– The Massachusetts Body of Liberties (1641), Section 47

The Massachusetts Body of Liberties codified many of the basic rights and privileges that we enjoy today. It had an early form of freedom of speech, and a right to petition the government with a “complaint.” It listed several rights of the accused; such as a protection from double jeopardy, a protection from forced confessions, and a protection from excessive bail. It gave them rights to a trial in criminal cases, and the right to an attorney to represent them in these trials. It gave them protections of life and property (as well as the right to challenge jurors), and some potent protections against any “inhumane Barbarous or cruel” bodily punishments. All of these things influenced the United States Bill of Rights, and it is hard to imagine life in this country without them. Our country would be in a much worse shape, if we didn't have these things. Thus, an examination of these rights would seem to be appropriate here. (I have decided to preserve the original spellings of its passages when quoting them, to give the reader something of their style and flavor.)

Friday, December 7, 2018

A review of “Tora! Tora! Tora!” (1970 movie)

“Thus, the earnest hope of the Japanese Government to adjust Japanese-American relations and to preserve and promote the peace of the Pacific through cooperation with the American Government has finally been lost. The Japanese Government regrets to have to notify hereby the American Government that in view of the attitude of the American Government it cannot but consider that it is impossible to reach an agreement through further negotiations.”

– Closing lines of the “Japanese Note to the United States,” on 7 December 1941 (which was delivered an hour after the Pearl Harbor attack, and did not contain an actual declaration of war anyway)

Pearl Harbor was part of a series of attacks throughout the Pacific …

On a warm Sunday morning in Hawaii, Japanese carrier planes attacked the United States fleet in Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941. But contrary to popular perception, this was not the only place that they attacked that day. The attack was actually simultaneous with moves elsewhere in the Pacific on places like British Malaya, British Singapore, and British Hong Kong. Prior to these attacks, neither the United States nor Britain had been at war with Japan; so these two countries were thus drawn into the Pacific theater of World War II at almost the same time. Other American possessions that were attacked at around this time were Guam, Wake Island, Midway Island, and the Philippines.

"Battleship Row" at Pearl Harbor (photograph taken from a Japanese torpedo plane, 1941)

Monday, November 19, 2018

A review of PBS's “Murder of a President” (James A. Garfield)

“I conceived of the idea of removing the President four weeks ago. Not a soul knew of my purpose. I conceived the idea myself. I read the newspapers carefully, for and against the administration, and gradually, the conviction settled on me that the President's removal was a political necessity, because he proved a traitor to the men who made him, and thereby imperiled the life of the Republic ... Ingratitude is the basest of crimes. That the President, under the manipulation of his Secretary of State, has been guilty of the basest ingratitude to the Stalwarts admits of no denial. ... In the President's madness he has wrecked the once grand old Republican party; and for this he dies.... I had no ill-will to the President. This is not murder. It is a political necessity. It will make my friend Arthur President, and save the Republic.”

– Charles Guiteau, in his letter to the American people, on 16 June 1881

On July 2nd, 1881, Charles J. Guiteau went to the Baltimore and Potomac Railway Station, and lay in wait for his intended murder victim. President James A. Garfield was scheduled to leave Washington D.C., and Guiteau wanted him dead before his train ever left the city. When President Garfield walked into the waiting room of the station, Charles Guiteau walked up behind him and pulled the trigger at point-blank range from behind. President Garfield cried out: “My God, what is that?”, flinging up his arms. Guiteau fired a second shot, and the president collapsed. One bullet grazed the president's shoulder, while the other struck him in the back. Guiteau put his pistol back into his pocket and turned to leave via a cab that he had waiting for him outside the station, but he collided with policeman Patrick Kearney, who was entering the station after hearing the gunfire. Kearney apprehended Guiteau, and asked him: “In God's name, what did you shoot the president for?” Guiteau did not respond. The crowd called for Guiteau to be lynched, but Kearney took Guiteau to the police station instead. (This paragraph borrows some exact wording from Wikipedia, which I should acknowledge here as a source.)

Contemporaneous depiction of Garfield assassination, with James G. Blaine at right

President Garfield with James G. Blaine in the railway station, shortly after the shooting

Sunday, November 11, 2018

A review of PBS's “The Great War” (American Experience)

“We [the German government] intend to begin on the first of February unrestricted submarine warfare. We shall endeavor in spite of this to keep the United States of America neutral. In the event of this not succeeding, we make Mexico a proposal of alliance on the following basis: make war together, make peace together, generous financial support and an understanding on our part that Mexico is to reconquer the lost territory in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona.”

– Zimmermann Telegram (1917), one of the events that led to the American entry into World War One

President Woodrow Wilson walked a tightrope during the early years of World War One, trying to steer a middle course between full neutrality and full involvement. Of course, Americans did not declare war on Germany until April 1917, and waited even longer than that to send troops to Europe. But even at the beginning of the war in 1914, most Americans did not want the Germans to win, and some of them actually sold food (and sometimes weapons) to the Allied nations. There was a massive peace movement before America officially got involved, and PBS makes sure to cover it here. But there were also many supporters of getting involved sooner - and this, too, receives some good coverage from PBS. Among the supporters of earlier American involvement was the former president Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt was a major critic of Wilson for his perceived lack of muscle in this struggle - a correct perception. But Wilson was also criticized by the peace movement for supporting aid to Britain and France. Thus, he was having a hard time walking this tightrope within his own party. Unfortunately for Wilson, this balancing act would prove even harder when the Germans sank the RMS Lusitania in 1915.

Sinking of the RMS Lusitania, 7 May 1915

Saturday, November 10, 2018

A review of PBS Empires “Martin Luther”

"Here I stand; I cannot do otherwise. God help me. Amen!"

- Martin Luther's "Speech at the Diet of Worms" (1521)

We take it for granted that the name “Protestant” comes from the word “protest.” But this name is a relic of a time when a “protest” against the establishment was more prominent. That establishment was then challenged by the distant thunder of revolution. It was just called the “Protestant Reformation” …

Wednesday, October 31, 2018

A review of Ken Burns’ “Baseball” (PBS)

“♪ Katie Casey was baseball mad,

Had the fever and had it bad.

Just to root for the home town crew,

Ev'ry sou

Katie blew. ♪

♪ On a Saturday her young beau

Called to see if she'd like to go

To see a show, but Miss Kate said 'No,

I'll tell you what you can do:' ♪ ”

– The unknown first verse of “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” (1908)

When Ken Burns' “The Civil War” came out in 1990, it was the most popular program in PBS history; and it still holds that record today. This program received significant critical acclaim, and it certainly deserved this acclaim. But when Ken Burns was asked what he was going to do next, he was met with raised eyebrows when he said “baseball.” For many people, baseball seems like something less than a “serious” historical topic; and probably seemed like a waste of Ken Burns' talent to boot. But to me, this is no “anticlimax” – this is a legitimate historical topic in its own right. You can learn a lot about the history of America by studying the history of its baseball, I think – at least, for the periods after baseball was invented. I will return to this theme multiple times in this post, as I give some related anecdotes from baseball history. Suffice it to say for now that it gives some great insights into this country; and that if you really want to understand America, you would do well to study this game in detail.

National League Baltimore Orioles, 1896

Christy Mathewson, known as “The Christian Gentleman”

Thursday, September 27, 2018

A review of “The Medici: Godfathers of the Renaissance” (PBS Empires)

“To the Magnificent Lorenzo Di Piero De' Medici:

Those who strive to obtain the good graces of a prince are accustomed to come before him with such things as they hold most precious, or in which they see him take most delight; whence one often sees horses, arms, cloth of gold, precious stones, and similar ornaments presented to princes, worthy of their greatness. Desiring therefore to present myself to your Magnificence with some testimony of my devotion towards you, I have not found among my possessions anything which I hold more dear than, or value so much as, the knowledge of the actions of great men, acquired by long experience in contemporary affairs, and a continual study of antiquity; which, having reflected upon it with great and prolonged diligence, I now send, digested into a little volume, to your Magnificence.”

– Dedication of Niccolò Machiavelli's “The Prince” (1532)

The rise of the Medici family owed much to the economic strength that they gained from banking

During this time, one family in particular rose to prominence in Italy – and more specifically, in Florence. In its heyday, this family produced kings, queens, and even three popes. That family was, of course, the Medici; but it did not start out as a royal family. Rather, it made its name through banking; and amassing wealth by means of the private sector. The rise of the Medici family owed much to the economic strength that they gained in this way. They actually started out their ascendancy as a family of Italian merchant-bankers, and continued to be such even during their political rule. They were among the earliest bankers in Europe, and were great pioneers in the banking industry. Their depositors stored their money in the “Medici Bank,” and the Medici then loaned out this money to people who needed it. The interest from these loans actually brought great wealth to the Medici family, and allowed them to pay some small interest to their depositors as well. It helped to create the family fortune, which brought them to political prominence in Italy. Money was often the greatest weapon in the Medici arsenal, and was a great driver of the politics of the Renaissance (as it was for every other era of human history).

Cosimo de Medici, the Italian banker who became the first of the Medici dynasty

Monday, September 17, 2018

The document that changed everything in America …

When the Founding Fathers wrote the original Constitution in 1787, they were creating a document that would change everything in America, keeping a fragile union of thirteen states from descending into war debts, bankruptcy, and even armed rebellions. One uprising in particular came from a disgruntled Revolutionary War veteran named Daniel Shays, whose uprising against the government of Massachusetts had been an impetus for holding the Constitutional Convention in the first place. It did not start out as a popular document, and was opposed openly even by some of the men who had been present at the Convention. Thus, the particulars of this document were debated fiercely from one end of the thirteen former colonies to the other.

George Mason

Luther Martin

What were the particulars of this document, and why did they create such an uproar when they were first written? What relevance might its passages have today, when our world is so different from the one they inhabited 200 years ago? What was it about this document that caused it to be so successful, and which made the country that adopted it into the greatest superpower that the world has ever known? And why is this most essential ingredient to the country's remarkable success story such an obscure and forgotten secret?

In this series, I will try to answer these questions, as I talk about everything from the people that influenced the Constitution (such as John Locke, and Baron de Montesquieu) to the men that commented on it (such as William Lloyd Garrison, and Abraham Lincoln). I will try to be informative, but I will not shy away from inserting persuasive commentary at times as well. I will lay out the case for why the Constitution of the United States is the greatest success story that human politics has ever known.

Tuesday, September 4, 2018

A review of “Rome: Rise and Fall of an Empire” (History Channel)

Note: This is a different series from “Ancient Rome: The Rise and Fall of an Empire” (which is made by the BBC).

There aren't too many documentaries out there about ancient history …

If you've ever looked online for movies about ancient history, you've probably had a hard time finding any. Ancient history isn't a popular subject for Hollywood movies (or even documentaries), and so very few programs about it have ever been made. I don't know why this has been the case, but I can probably make some guesses about it. If you make a documentary about World War II (a modern topic), you have access to actual archival footage from the period. You can get it at very low cost, and advertise its benefits to your viewers. Some of them will even prefer the gritty realism of the actual footage to re-enactments, which are just educated guesses (albeit good ones, if they're done right). Thus, you can sometimes get more effectiveness for less money, which is a real advantage in the world of documentaries. But if you depict the distant past, you are usually forced to rely on re-enactments, and the cost of these re-enactments can be steep. Consequently, many of these ancient history documentaries are never made in the first place.

This documentary is primarily a military history

An ancient history topic must thus be fairly popular before a for-profit network like the History Channel will decide to throw significant money at it. No matter how much the producers of these networks might like these topics, they usually can't justify the budget for these programs unless they think that they have a reasonable chance of recovering these expenses with some added cash flow. One presumes that the Roman Empire was considered popular enough to justify these budgets to investors at this time. If it had not been, after all, it's safe to assume that this series would never have been made. I imagine part of its appeal to the general public was its focus on military history (rather than other kinds of history). Military history has long been a popular topic with certain segments of the general population (perhaps especially the male population); and although political history is sometimes covered here, the primary focus of this series is military history. This may be the most comprehensive military history of Rome ever made for television. It has some weaknesses (which I will note later), but it's still a fine series despite these.

Relief scene of Roman legionaries marching, from the Column of Marcus Aurelius – Rome, Italy, 2nd century AD

Wednesday, August 29, 2018

David Hume criticized social contract theory severely …

“My intention here is not to exclude the consent of the people from being one just foundation of government where it has place. It is surely the best and most sacred of any. I only pretend, that it has very seldom had place in any degree, and never almost in its full extent. And that therefore some other foundation of government must also be admitted.”

– David Hume's “Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary” (1752), Part II, Essay XII (entitled “Of the Original Contract”)

Do governments require the “consent of the people”? If you think they do, you might be a believer in social contract theory, even if you don’t realize it yet. The idea that governments have actual duties to their people, and not just people having one-way duties to their governments, is at the foundation of every democracy; and is at the heart of social contract theory in every way.

United States Capitol

What is social contract theory, and why is it important?

In a nutshell, this social contract theory is basically the idea that there is an agreement between government and the people, which believers in this theory may or may not believe to have been written down on paper. In this agreement, it is held that governments agree to do certain things for their people, and that the people agree to do certain things for their society. These would include obeying the laws that their governments are actually authorized to make under this agreement – although not all laws would be authorized by these agreements, since some of these laws might be considered “unconstitutional” under its terms. (More on that later in this post – for now, I will just explain what social contract theory is at its most basic level.) What exactly the duties of each party might be is a matter of some controversy, I should acknowledge here, even among social contract theorists. Thus, I will not attempt here to specify numerous details of the duties owed by either side in this agreement. This would be too long a task for a single blog post, in fact, and would be beyond the scope of a blog like mine. Rather, I will attempt to show how social contract theory influenced the United States Constitution (since I am an American), and show how our own Constitution owes much to the English philosopher John Locke in this regard, since he was a great social contract theorist in a previous century. (For more on the basics of this theory, I will refer interested readers to another of my blog posts, which I link to here. This post will focus more on how this theory has been applied in actual practice, at least in my own country.)

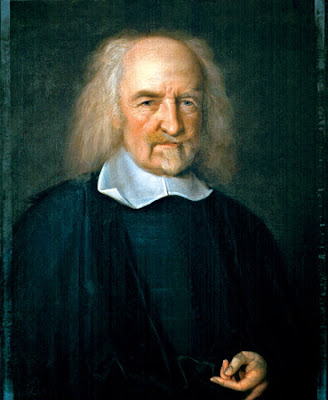

Thomas Hobbes

How did Locke’s social contract theory influence the Constitution?

“Bills of attainder, ex-post-facto laws, and laws impairing the obligation of contracts, are contrary to the first principles of the social compact, and to every principle of sound legislation.”

– James Madison, in the Federalist Papers (Federalist No. 44)

David Hume criticized the idea that all governments began by a “social contract” …

The philosopher David Hume once criticized social contract theory for saying that all governments began by an actual social contract (see my previous blog post for the details of this quote). In his “Essays, Moral, Political, Literary,” for example, he said that this account was “not justified by history or experience, in any age or country of the world.” (Source: Part II, Essay XII – entitled “Of the Original Contract”) Some of Hume's criticisms of the theory of social contracts may be valid (including this one), and the idea that all governments actually began in this way is indeed unsupported by the historical evidence, as Hume said. Many social contract theorists have actually agreed with this much, and have modified their theories accordingly to accommodate this criticism. They say that the “social contract theory” is still a workable model even without this claim that governments actually began in this way.

David Hume

… but the Constitution is itself a “social contract”

But regardless of the historical origins of government (which I have discussed earlier), one might note with some satisfaction that some “social contracts” really have been enacted between government and their people, and that the Constitution itself was one of these “social contracts” (even if it was after Hume’s time, which it was). People agreed to obey the laws by creating a government that had the power to make them, and which had the power to punish violations of those laws via some particular clauses in the document. The people also agreed to pay taxes, and to do a few other things which I will not elaborate upon in this post. In return, the government agreed (not always very truthfully) to refrain from doing certain things, and to consider itself in violation of these laws anytime that it did them anyway. (Even government is not above the laws, as the Founding Fathers made clear.) Our Constitution was thus an application of social contract theory, which came from the writings of people like John Locke.

John Locke

Some have questioned whether Locke was an influence on the Constitution …

Some have questioned today whether John Locke had much of an influence on the Constitution. The political scientist Donald Lutz, for example, said that “Locke is profound when it comes to the bases for establishing a government and for opposing tyranny, but has little to say about institutional design. Therefore his influence most properly lies in justifying the revolution and the right of Americans to write their own constitutions rather than in the design of any constitution, state or national. Locke's influence has been exaggerated in the latter regard, and finding him hidden in passages of the U.S. Constitution is an exercise that requires more evidence than has hitherto ever been provided.”(Source: The American Political Science Review, Vol. 78, No. 1, March 1984, p. 192-193) I have a lot of respect for Donald Lutz, I should make clear, and have actually quoted him elsewhere in this series as an authority on what influenced the Founding Fathers. But I nonetheless must disagree with him on this particular point, and hold that Locke influenced particular passages in the Constitution. In fairness to Mr. Lutz, I should acknowledge that he did not question that Locke was influential on the Founding Fathers, even in this quote – indeed, he believed that Locke was quoted by the Founding Fathers more than any other thinker, besides Montesquieu or William Blackstone. But I will endeavor to show some evidence here that Locke influenced our Constitution, and that his influence can be found in particular passages within the document.

John Locke

Friday, August 24, 2018

A review of “Ancient Rome: The Rise and Fall of an Empire” (BBC)

Not to be confused with “Rome: Rise and Fall of an Empire” (by the History Channel).

“Ancient Rome: The Rise and Fall of an Empire” is neither a documentary nor a history. It uses too many re-enactments (and too little narration) to be considered a traditional documentary, and it is too sporadic and episodic to be considered a history. It does not observe the chronology well enough to be considered a true history of Ancient Rome. One episode in particular is out of chronological order, and even the others only cover brief episodes in Roman history. The gaps between them are measured in decades (and sometimes even centuries), so nothing like a comprehensive overview is even attempted. However, we should not conclude from these things that the BBC's efforts are without merit here. On the contrary, they have much to offer for the Roman Empire buff and the student of history. They even succeed in being entertaining, and bringing these events to life – which is not a small consideration, for a program on public television.

Sunday, August 19, 2018

A review of “The Roman Empire in the First Century” (PBS Empires)

“And it came to pass in those days, that there went out a decree from Cæsar Augustus, that all the world should be taxed.”

- The New Testament, “The Gospel According to St. Luke,” Chapter 2, Verse 1 (as translated by the King James Version of the Bible)

Since this documentary was first shown in 2001, there have been a few other documentaries made about Ancient Rome. These include a six-hour program by the BBC, and a ten-hour program by the History Channel. By contrast, this PBS program is only four hours long, so you might expect it not to be as “in-depth.” If so, you'd be wrong; because these other programs cover much broader time periods than just the first century. This gives them an advantage over PBS in these other periods, but it also means that they can't cover this narrower period in as much depth as PBS does. If it's the first century you're after, this is definitely the documentary to go to; and so it has a lot to offer in this regard. Nonetheless, all of these programs add something to one's knowledge of the history; so the true Roman Empire buff will probably want to consult all of them. If you prefer dramatizations with lots of re-enactments, the BBC and the History Channel are probably more up your alley than this PBS program. But if you like period images (including statues and archaeological sites), you will find much to enjoy in this documentary by PBS.

Friday, August 17, 2018

How my views on government are influenced by my faith

“That our belief with regard to earthly governments and laws in general may not be misinterpreted nor misunderstood, we have thought proper to present, at the close of this volume, our opinion concerning the same.”

- Heading to Section 134 of “The Doctrine and Covenants of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints” (written 1835)

I am a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, which influences how I see the world …

Since the presidential elections of 2012, Latter-Day Saint candidates have featured prominently in the United States. People who normally have no interest in hearing about The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints would sometimes make exceptions for hearing about Latter-Day Saint candidate Mitt Romney, because of his being the Republican presidential nominee. Ironically, the church has long made it clear that it “does not endorse, promote or oppose political parties, candidates or platforms,” and that it does not “attempt to direct its members as to which candidate or party they should give their votes to.” (Source: The Mormon Newsroom). However, it does speak out on some political issues at times, and its scriptures include some prominent beliefs about governments and laws. Thus, I thought I would go over these beliefs about governments and laws here, and allow people outside the church to hear them (if they so choose) from a practicing member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints.

American flag

Monday, August 13, 2018

Behind the Iron Curtain: Occupation by the Soviet Union

"While the Wall is the most obvious and vivid demonstration of the failures of the Communist system - for all the world to see - we take no satisfaction in it; for it is, as your mayor [of West Berlin] has said, an offense not only against history but an offense against humanity, separating families, dividing husbands and wives and brothers and sisters, and dividing a people who wish to be joined together."

- American president John F. Kennedy, in his "Ich bin ein Berliner" speech (June 26, 1963)

World War II had just ended; but for parts of Eastern Europe, the nightmare was just beginning ...

During the Second World War, Eastern Europe was unfortunately caught in the crossfire between Hitler's Nazi Germany and Stalin's Soviet Russia. Conquest by either one meant certain tyranny and subjugation, but to be caught on the losing side of this struggle for the Eastern Front would mark one's country for revenge, terrible and swift. It was not known yet who would be the winner, and the two sides were so ruthless to begin with that any additional punishment from the eventual victor was a terrifying prospect for them. Perhaps partially for this, the nations of Eastern Europe decided to choose sides in this struggle, hoping to promote their interest; and some paid a heavy price for making the wrong choices in these matters. But all were doomed to suffer in one way or another, and even the ones whose alliances had actually served their interest in these years were condemned to suffer in a communist occupation later on, regardless of which side they had served at this earlier time. The eventual winner on the "Eastern Front" was, of course, Soviet Russia; and it imposed its will without any mercy on the nations that it had conquered.

Red Army raises Soviet flag in Berlin after taking the city, May 1945

Some parts of Eastern Europe were already occupied before World War II

To be clear, some of these nations were already conquered before the war started, and some had been part of the "Union of Soviet Socialist Republics" (or "USSR") since the moment of its creation in 1922. (This is the political entity that is better known today - and was known then - as the "Soviet Union.") They were thus already puppet states that had been annexed by the USSR. Others became puppet states that were made part of the Soviet Union in 1940 - after World War II had begun in Europe, but before the Soviet entry into the war in 1941. These states were annexed at this time instead. Others became puppet states much later on in the war - or even after, in some cases. Although some of these states were never actually annexed into the Soviet Union - possibly to create the illusion that the Russians were actually keeping their World War II treaty promises of non-interference - they were nonetheless controlled from Moscow as much as any of the others. These included Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Hungary, Poland, and Romania - and, for a brief time, Yugoslavia and Albania. (More on the special status of these two nations later in this post.) Together with the Soviet states, these nations were all then part of what was called the "Eastern Bloc." For these nations, the ordeal of Soviet occupation began during - and in some cases, after - World War II, and the long nightmare of "no peace" would be followed by the even longer nightmare of no freedom. It is these nations that I will focus on here, since their distance from the center of Soviet power encouraged them to attempt more revolts against the communist occupation - revolts that (unfortunately), before 1989, did not succeed.

Border changes in the Eastern Bloc, from 1938 to 1948

Monday, August 6, 2018

Why dropping the bombs on Japan was the RIGHT thing to do

“We the undersigned, acting by authority of the German High Command, hereby surrender unconditionally to the Supreme Commander, Allied Expeditionary Force and simultaneously to the Supreme High Command of the Red Army all forces on land, at sea, and in the air who are at this date under German control.”

– “Act of Military Surrender Signed at Berlin,” on 8 May 1945

Nazi Germany had just surrendered, but the war in the Pacific continued in full force …

In May 1945, Nazi Germany finally surrendered to the Allies. It was a day of great rejoicing, and the Allies had cause to rejoice at that time. But the Second World War was not yet over, because there was another conflict going on in the Pacific. That conflict was with Japan; and it continued to produce American casualties as a great battle raged at Okinawa. My grandfather was fighting there at Okinawa, and he was among a number who were psychologically scarred by the experience. Others were physically scarred, and others were sent home in coffins, never to be heard from again (or seen alive again). Okinawan civilians jumped off cliffs at this time, in the “certain” knowledge that they would be mistreated by the Americans. The few survivors were glad to find out that the Americans were much nicer than the Japanese propaganda films had portrayed them to be; but many a Japanese soldier preferred suicide to surrender, and actually committed suicide at this time. If we had been forced to invade the Japanese home islands, it seems that this scenario would have been repeated time and time again, with the same grim costs in human life. Such was the wisdom of instead bombing Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

US Marines pass a dead Japanese soldier in a destroyed village - Okinawa, April 1945

Saturday, July 21, 2018

A review of “Kingdom of David: The Saga of the Israelites” (PBS Empires)

“And David perceived that the LORD had confirmed him king over Israel, for his kingdom was lifted up on high, because of his people Israel.”

- The Hebrew Bible, “The First Book of the Chronicles,” Chapter 14, Verse 2 (as translated by the King James Version of the Bible)

The title of this documentary is only partially correct – it's not about the “Kingdom of David”

The title of this documentary is only partially correct. This is indeed “The Saga of the Israelites,” but it actually has very little coverage of the “Kingdom of David” itself (although it's still a great documentary despite this). It is actually a documentary on a different topic, and has a broader focus than the brief “Kingdom of David.” It instead covers a much broader period of history, including Judaism's clashes with the Greeks and Romans. If you go into this documentary expecting its title to be accurate, you may thus be somewhat disappointed. But this documentary has much to offer despite these things, and covers some history that you may not have heard about. A few Americans will have already heard these stories, I think, but I suspect that most have not; and I was definitely in this category before watching this. I think that I can recommend this documentary to everyone – both Jews and Gentiles.

Monday, July 16, 2018

Bedtime stories about Armageddon: The lessons of the Cold War about nuclear weapons

“I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture … ‘And I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.’ I suppose we all thought that, one way or another.”

– Julius Robert Oppenheimer, speaking of the “Trinity” explosion (1945), the first nuclear detonation

The Americans were the first to acquire (and later use) nuclear weapons

In July 1945, the world's first nuclear detonation went off in the American state of New Mexico. The explosion was in the desert near Alamogordo Bombing and Gunnery Range. (This area is now part of White Sands Missile Range.) This was near the end of World War II, and the Cold War had not yet begun at this time. But it would have massive importance in the coming struggle with Soviet Russia. In August 1945, the Americans dropped two atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which would have an even greater effect on the coming conflict. The frightening effects of these two bombs would haunt the world throughout the Cold War, as a chilling warning of what would happen if they were on the receiving end of a nuclear attack. Indeed, the nuclear weapons first introduced in 1945 were the most important aspect of the global confrontation now known as the “Cold War.” It is the biggest reason why the two major superpowers – which were the United States and the Soviet Union – did not directly engage each other in open conflict on a battlefield, except on a few rare occasions (which I will not elaborate on here).

“Trinity” explosion - New Mexico, United States (16 July 1945)

Why is it called the “Cold War,” when there were so many “hot wars” within it?

The reason that we call it the “Cold War” is that most of the time, the conflict did not involve actual shooting; which would be more characteristic of a “hot war.” Instead, it was usually just a “cold war” with the threat of a nuclear holocaust – although there were some notable exceptions where actual shooting occurred. (Such as the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and the Soviet war in Afghanistan; which were all part of the larger “Cold War.”) This post will not attempt to cover these “hot wars” within the Cold War, and it will not attempt anything like an overview of this massive worldwide conflict. Rather, it will focus on the most important aspect of it, which is nuclear weapons. (Although if you're interested in the other parts of the Cold War, I cover some of them elsewhere on this blog here, for anyone that is interested.) Despite the problems caused by nuclear weapons since their first introduction in 1945, it is well that the Americans (and the free world generally) got this technology before the Nazis or the communists did, sine the prospect of these regimes getting the bomb first would have been chilling indeed. (And the Nazis almost did get it before the Americans did.)

Hiroshima explosion (left) and Nagasaki explosion (right), 6 and 9 August 1945

Tuesday, July 10, 2018

Blackstone quoted in Federalist Papers: The influence of Blackstone's “Commentaries”

"The observations of the judicious Blackstone,1 in reference to the latter; are well worthy of recital: 'To bereave a man of life,' says he, 'or by violence to confiscate his estate, without accusation or trial, would be so gross and notorious an act of despotism, as must at once convey the alarm of tyranny throughout the whole nation; but confinement of the person, by secretly hurrying him to jail, where his sufferings are unknown or forgotten, is a less public, a less striking, and therefore A MORE DANGEROUS ENGINE of arbitrary government.' And as a remedy for this fatal evil he is everywhere peculiarly emphatical in his encomiums on the habeas-corpus act, which in one place he calls 'the BULWARK of the British Constitution.'2"

- Alexander Hamilton, in the Federalist Papers (Federalist No. 84)

Blackstone was on the other side of the Revolutionary War from our Founding Fathers ...

When the United States declared independence from Britain, it was not breaking with its British heritage to the degree that you might have expected then. The Magna Carta, the Petition of Right, and the English Bill of Rights remained influential in the thirteen states, you see. Ironically, one of the prior philosophers that most influenced our Founding Fathers was on the other side of the Revolutionary War from them, and he remained loyal to the British side even until his death in 1780 (five years into the War of Independence which had not yet ended). He had once received the patronage of Prince George, who later became "King George III" - the nemesis of the Revolution.

William Blackstone

... but his name still appears in the Federalist Papers no less than five times

This great philosopher was William Blackstone (of Blackstone's "Commentaries"), and he wrote his "Commentaries on the Laws of England" in 1765 - ten years before the first shots of the Revolution were fired at Lexington and Concord. The four volumes of Blackstone's "Commentaries" were virtually required reading for students of the law in English-speaking countries. They thus had a powerful influence on these countries' legal traditions, and they were sometimes the only law books that lawyers on the frontier could read. In a young republic without a long-standing legal tradition of its own, they were the most influential description of these laws of the mother country. Mr. Blackstone was a powerful influence on the Founding Fathers even despite his being on the other side of the war from them, and his name actually appears in the Federalist Papers no less than five times. He continues to be quoted in Supreme Court decisions in America, and he influenced several generations on the American frontier (including a country lawyer named Abraham Lincoln). But it is his influence on the founding of our country - and specifically, on the writers of the Federalist Papers - that I will be discussing here.

Tuesday, June 26, 2018

The Second Amendment: Protecting the gun rights “of the people”

"A well-regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed."

- Second Amendment to the United States Constitution (ratified 1791)

Does the Second Amendment apply only to the "militia," or to the whole "people"?

The Second Amendment says that "the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed" (Source: Second Amendment). Supporters of the right to "bear arms" have long pointed to this portion of the amendment as evidence for legal gun rights possessed by individuals. But gun control advocates point with equal fervor to the prior clause of this amendment, which said that "A well-regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free State ... " (Source: Second Amendment). They argue that this mention of the phrase "militia" somehow means that the gun rights apply only to the country's armed forces, and therefore cannot be legitimately possessed by the whole "people." If this argument is to be believed, then it would seem that there couldn't have been much of a distinction between the "militia" and the "people," or this latter clause about the "right of the people" would have been a non sequitur that didn't follow from the previous clause (which was presumably supposed to support it, if this amendment's context is any clue here). But there is now a greater distinction between the two than there was then, because the term "militia" is currently understood in a very narrow sense that didn't apply at the time that this amendment was first written.

"Brown Bess" musket and bayonet, which was used in the American Revolution

What distinctions did the Founding Fathers make between the "militia" and the "people"?

Because of this, gun control advocates maintain that a constitutional right to "bear arms" applies only to a narrow portion of the country's population. Thus, they argue, it cannot be understood to apply broadly to the whole "people," as people like me would hold. Thus, it would seem appropriate to correct the record here, and to show that the term "militia" was actually understood to mean something broader when this amendment was written. Gun control advocates may be partially correct in one respect, I should acknowledge here, when they say that not everyone was always included under the term "militia." Nonetheless, this definition was much broader than contemporary interpretations would usually admit today. In the context of the amendment itself, it is clear that it was never intended to be restricted to the "militia" anyway (as I will show later). But even if it was, the concept of a "militia" can be shown to be much broader than the mere armed forces of this country. It should thus be understood broadly today, if the original intent of the amendment is to be upheld.

American infantry in the Revolutionary War

Friday, June 15, 2018

A review of David Starkey's “Monarchy” (U. K.)

"God save our gracious King!

Long live our noble King!

God save the King!

Send him victorious,

Happy and glorious,

Long to reign over us:

God save the King!"

- "God Save The King" (alternatively, "God Save The Queen"), adopted as the national anthem of the United Kingdom in 1745

Throughout the English-speaking world, people are fascinated by the British monarchy. Although the institution has very little power today, Americans still follow its every move, as though we had never fought a revolution against it. Despite all of this interest, there has sometimes been a trend in recent years - amongst historians, at least - to try and focus on what happened to "ordinary people" in history, and focus less on the traditional subjects of "politics and the military." For example, Ken Burns once said that the history of the United States is usually told as "a series of presidential administrations punctuated by wars," and that all other aspects of American history - including those dealing with ordinary people - are given short shrift, or even lost entirely. There is truth in this claim, and there is value in focusing on the lives of ordinary people - and on other celebrities from other areas. Why, then, do we focus so much on powerful political leaders? Why do we continue to be fascinated by the lives of kings and queens, when the "common man" is held up as the "greater ideal" for an enlightened democracy?

Queen Victoria

Why do we sometimes ignore the "ordinary people" of history?

I think part of it might be that the lives of ordinary people are usually not as well-documented as the lives of the rich and powerful. Thus, a dig by archaeologists that unearths details of an ordinary person's life doesn't get as much fame and sexiness as those that unearth details of a major monarch's life. For example, most people would rather hear more about Julius Caesar and his generals, than about the ordinary men and women that made up the empire he ruled. The same is true of American presidents and generals. But besides the fact that the lives of ordinary people are not as well-documented, there is another reason that historians focus so much on politics and the military (including monarchy). This is that the lives of ordinary people are affected quite extensively by what genius - or moron - is in power at the moment. For the history of most countries of the world, this necessarily entails a thorough examination of kings, queens, and royal families - on the monarchs and dynasties who are in charge at any given time. These kings are not just studied because historians are fans of royalty and juicy court gossip, although there is plenty of that. Rather, it is because the history of entire countries depends on these things, and on the "royal soap operas" that are so often found at the center of power.

Queen Elizabeth the First

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)