"The political liberty of the [citizen] is a tranquillity of mind, arising from the opinion each person has of his safety. In order to have this liberty, it is requisite the government be so constituted as one man need not be afraid of another."

- Baron de Montesquieu's "De l'esprit des lois" ("The Spirit of Laws") [published 1748], Book XI, Chapter 6

Montesquieu had some important ideas about how to prevent tyranny (and they're still relevant today)

The U. S. Declaration of Independence owed much to the work of John Locke, the English political philosopher. But the political scientist Donald Lutz said that "If there was one man read and reacted to by American political writers of all factions during all the stages of the founding era, it was probably not Locke but Montesquieu." (Source: The American Political Science Review, Vol. 78, No. 1, March 1984, p. 190) This is not to deny the importance of Locke, as he was also an enormous influence on the Founding Fathers (see my blog post for evidence of this). Nonetheless, Montesquieu is definitely the author that had the greatest influence on both sides of the ratification debates, and perhaps even on the finished product of the United States Constitution itself. He's almost like a Founding Grandfather of the United States, his influence is so strong. This is why I recently finished reading his most famous work "De l'esprit des lois" ("The Spirit of Laws") in the original French. He was a Frenchman, who wrote his most famous work in 1748 - a book written over a quarter of a century before the American Revolution. This book was one of the most important influences on the Founding Fathers.

Baron de Montesquieu

How to prevent bad government: Keep any one group from getting too much power

Montesquieu is probably best known today for his important theory of a separation of powers in government. Put briefly, this theory is the idea that bad government is best prevented by keeping any one group from getting too much power over the others. James Madison referenced this danger in the Federalist Papers by saying that "the accumulation of all powers, legislative, executive, and judiciary, in the same hands, whether of one, a few, or many, and whether hereditary, self-appointed, or elective, may justly be pronounced the very definition of tyranny." (Source: Federalist No. 47) Hence, the need for a system of government that divides up these powers as much as possible. This is something that the United States Constitution does by dividing up this power into three branches of government - the legislative, executive, and judiciary. The legislative branch makes the laws, the executive branch enforces the laws, and the judiciary branch judges and interprets the laws, with as little overlap between these three kinds of power as possible. (More on that in a separate post - for now, I will confine myself to talking about the specifics of the theory, at least in basic form.)

United States Constitution

Concentrated power is inherently dangerous, and leads to disastrous tyranny and oppression

It might be helpful here to give a few words from Montesquieu himself about this theory, which describe the dangers inherent in concentrated power: "When the legislative and executive powers are united in the same person or body," he said, "there can be no liberty, because apprehensions may arise lest the same monarch or senate should enact tyrannical laws to execute them in a tyrannical manner." Again: "Were the power of judging joined with the legislative, the life and liberty of the subject would be exposed to arbitrary power, for the judge would then be the legislator. Were it joined to the executive power, the judge might behave with all the violence of an oppressor." (Source: "The Spirit of Laws," Book XI, Chapter 6) Thus Montesquieu gives at least some specifics on how the disasters that he predicted would follow such a concentration of power would come to pass; and the specific results for every possible combination of those three kinds of power - legislative/executive, judicial/legislative, and judicial/executive. It might be helpful to mention here that James Madison actually quoted these passages in the Federalist Papers - in an English translation, of course. The translation that I offer here is the one that was used by James Madison there. (Source: Federalist No. 47)

James Madison

The oracle on this subject is "the celebrated Montesquieu"

One of the interesting things about Montesquieu's publication of this theory in "The Spirit of Laws" is that at the time he wrote it, the most famous document in history to apply this doctrine - which is none other than the United States Constitution - did not exist yet. Thus, it was not available to hold up as a model for how this theory was to work in practice. The reason is that "The Spirit of Laws" influenced the Constitution, not the other way around. Rather, Montesquieu paved the way for the Founding Fathers to use this theory by giving it a good justification in "The Spirit of Laws" that was intellectually respectable, and which is still quoted today in universities. This caused James Madison to say with some justification in the Federalist Papers that "The oracle who is always consulted and cited on this subject is the celebrated Montesquieu. If he be not the author of this invaluable precept in the science of politics, he has the merit at least of displaying and recommending it most effectually to the attention of mankind." (Source: Federalist No. 47) This is a testament to the influence of Montesquieu.

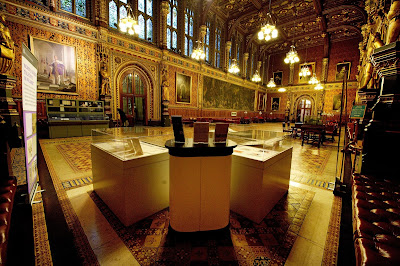

British Parliament

The British government was the model for Montesquieu, which he used as evidence for his theory

Another interesting thing about Montesquieu's advocacy for this theory is that even though his book actually predated the Constitution by a few decades or so, at least one example did already exist at that time of a separation of powers in practice. This was none other than the British government - which divided powers capably between the King and the Parliament. It was not as perfect an example of this concept as the later United States Constitution was, but it was nonetheless a potent piece of empirical evidence that Montesquieu could hold up, as an example of how he wasn't just "making these things up." He could actually cite historical examples of how nations that practiced this principle were successful, and nations that did not were not successful. (In ancient times, the Greek historian Polybius also noted the remarkable success of the Roman Republic in his native Hellenistic period, and attributed this success to its separation of powers - or in his phrase, its "mixed constitution." Polybius may thus have been the true author of this "invaluable precept in the science of politics," to use Madison's phrase. More about Polybius's contributions here.) I might note for my readers one other thing about the British government here, which is that it seems that no theory of democracy caused it to exemplify this practice at first. Rather, it seems to have been the accidental result of compromises between Britain's kings and parliaments wrought by war. The ironic thing about this is that it actually worked better than any deliberate design of human beings could have come up with before that time. History seems to have discovered this principle accidentally before people realized how good it really was.

Alexander Hamilton

The need for checks & balances between the branches to make this all work

The other part of this theory of a separation of powers is the idea of checks and balances. This is the idea that power must not only be balanced among different branches of government, but that each branch must have some power to "check" the excesses of the others. In other words, they must have the power to prevent the other branches from overstepping their bounds by giving them the power (and incentives) to stop the encroachments of the others. The particulars of this theory are actually quite complex, so I will content myself with saying here that such things are necessary to preserve a separation of powers in practice. Alexander Hamilton made reference to these "legislative balances and checks" in the Federalist Papers, when he said that "The science of politics, however, like most other sciences, has received great improvement. The efficacy of various principles is now well understood, which were either not known at all, or imperfectly known to the ancients. The regular distribution of powers into distinct departments; the introduction of legislative balances and checks; the institution of courts composed of judges holding their offices during good behavior; the representation of the people in the legislature by deputies of their own election: these are wholly new discoveries, or have made their principal progress towards perfection in modern times. They are means, and powerful means, by which the excellences of republican government may be retained and its imperfections lessened or avoided." (Source: Federalist No. 9) Thus, the Federalist Papers made clear that the Founding Fathers were influenced by this part of his theory as well, and applied it in a multitude of ways in the writing of the Constitution. (See my later chapters about the Constitution for further details on this.)

Constitutional Convention, 1787

Saying that this leads to "gridlock" misunderstands the entire purpose of checks & balances

One last point needs to be made: Some modern critics of the United States Constitution have argued that separation of powers sometimes leads to "gridlock." By this, it is usually meant that the three branches - particularly the legislative and executive branches - don't often agree with each other on anything. Thus, they argue that nothing useful is accomplished when they use their "checks and balances" to stop the actions of the other two branches. This "separation of powers," according to this group, thus leads to conflict which is "destructive" - or, at least, "unproductive." To me, this misunderstands the entire purpose of "checks and balances." It is true that less legislation is passed when the two houses of Congress disagree with each other or with the president, but this often means that less bad legislation is passed, too. Thus, this so-called "gridlock" is actually a potent protection against ill-advised (or hasty) government action. This is because it requires widespread agreement among the different parts of the government before any major changes can be undertaken.

United States Capitol

The disagreements involved here do not so much produce conflict as reflect it, and give it a voice

Furthermore, it would seem that the inevitable disagreements involved here do not so much produce conflict as reflect it, giving it a voice in a democratic process. Any conflicts within the government will have their origins in those possessing the power to elect them - namely, the people at large, whose conflicts predate their expression at the ballot box. The ultimate expression also creates a dialogue between the groups that is more often productive than destructive, and which is essential to any society that truly values the voice of each individual. The only way to eliminate gridlock, it would seem, would be to concentrate all of the power in one place; so that there couldn't be any multiple decision-makers disagreeing with each other on anything. Such a solution would remove the gridlock, it is true, but it would also remove our freedom. Thus, it would be worse than the problem that it is supposed to cure (to put it mildly). All things considered, checks and balances would thus seem the best way to go. They would prevent any disastrous concentrations of power in one particular place - something which would be too dangerous to be worth any benefit that might be imagined to come from it.

Capitol Dome

Separation of powers makes it so that "one man need not be afraid of another"

Because of the theories discussed in this post, Montesquieu has gone down in history as one of the greatest political philosophers. The Constitution whose foundations he laid continues to be the "supreme law of the land" for the United States of America, the most powerful nation in the world. His warnings about the dangers of concentrated power are thus as relevant today as they have ever been. The continued American success story shows that the remedy that he advocated for this problem (a separation of powers) works in practice. It maintains the nations that practice it in their freedom. It daily protects them from the dangers of tyranny, and makes it so that "one man need not be afraid of another."

Some quotes from the United States Constitution about separation of powers:

"All legislative powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Senate and House of Representatives." - Article 1, Section 1

"The Executive power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America." - Article 2, Section 1

"The judicial power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme court, and in such inferior courts as the Congress may, from time to time, ordain and establish." - Article 3, Section 1

If you liked this post, you might also like:

How the United States Constitution accomplished a separation of powers

5 limits on presidential power that you never heard of

Some of the credit for "separation of powers" should go to Polybius

Montesquieu quoted in Federalist Papers: "Confederate republics"

Montesquieu quoted in Federalist Papers: Separation of powers

Do checks and balances conflict with separation of powers?

The tyrannical police state: The worst nightmare of the Founding Fathers

Reading Alexis de Tocqueville's "Democracy in America" in French

Part of a series about

Political philosophy

Baron de Montesquieu’s “The Spirit of Laws”

Others to be covered later

Part of another series about the

U. S. Constitution

Introduction

Influences on the Constitution

Hobbes and Locke

Public and private property

Criticisms of social contract theory

Responses to the criticisms

Hypothesized influences

Magna Carta

Sir Edward Coke

Fundamental Orders of Connecticut

Massachusetts Body of Liberties

Sir William Blackstone

Virginia Declaration of Rights

The Declaration of Independence (1776)

Representative government

Polybius

Baron de Montesquieu

Articles of Confederation

The Constitution itself, and the story behind it

Convention at Philadelphia

States' rights

The Congress

Congress versus the president

Powers of Congress

Elected officials

Frequency of elections

Representation

Indigenous policies

Slavery

The presidency

Impeachment and removal

The courts

Amendment process

Debates over ratification

The "Federalist Papers"

Who is "Publius"?

Debates over checks & balances

The Bill of Rights

Policies on religion

Freedom of speech and press

Right to bear arms

Rights to fair trial

Rights of the accused

Congressional pay

Abolishing slavery

Backup plans

Voting rights

Epilogue

← Previous page: Polybius - Next page: Articles of Confederation →

No comments:

Post a Comment