"A person charged in any state with treason, felony, or other crime, who shall flee justice, and be found in another state, shall, on demand of the executive authority of the state from which he fled, be delivered up, to be removed to the state having jurisdiction of the crime."

- Article 4, Section 2, Paragraph 2 of the Constitution

Headquarters of the United States Department of Justice, or "DOJ"

Although the president enforces the laws, they can't punish people without the courts ...

In our Constitution, it says that the president "shall take care that the laws be faithfully executed, and shall commission all the officers of the United States" (Source: Article 2, Section 3). This includes prosecutors and police officers. Many of these laws to be "faithfully executed" authorize particular punishments for various actions, from fines to imprisonment to being executed (depending on the seriousness of the offense, as perceived by the Congress). If the president had carte blanche to enforce these laws passed by Congress, with no limits to this power, he could carry out these punishments anytime that he said these laws were violated - or even at times when they were not. (If, that is, there were no judicial branch to check this power, and require him to prove that these violations actually happened as he claimed they did.) Thus the Constitution created a judicial branch that was as independent as possible from the President and the Congress, so that no one group would possess the power to enforce these laws at their own whim or fancy. This is one of the real bulwarks of our Constitution, and is one of the true guarantees of our liberties. Thus, I wish to spend some time on it in this post, and educate us all about our constitutional rights as American citizens - particularly those found in the Bill of Rights.

Supreme Court of the United States

... so the very existence of the court system is itself a check on the presidency

Specifically, the Constitution said that "The judicial power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme court, and in such inferior courts as the Congress may, from time to time, ordain and establish. The judges, both of the supreme and inferior courts, shall hold their offices during good behaviour, and shall, at stated times, receive for their services a compensation, which shall not be diminished during their continuance in office." (Source: Article 3, Section 1) The courts have a certain power to strike down laws passed by the Congress, which is another important power that I should note (at least in passing) before moving on to my main topic, which is judicial restraints on the president and the police force. (I discuss striking down laws in some detail in one of my other blog posts, if you're interested in that subject. This post, by contrast, will be more focused on the Bill of Rights, and on the judicial checks on the executive branch.)

U. S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals (an influential appeals court) - Pasadena, California

Jurisdiction of the supreme court vs. the inferior courts

The Constitution clarifies the courts' jurisdiction when it says that "The judicial power shall extend to all cases, in law and equity, arising under this constitution, the laws of the United States, and treaties made, or which shall be made under their authority; to all cases affecting ambassadors, other public ministers and consuls; to all cases of admiralty and maritime jurisdiction; to controversies to which the United States shall be a party; to controversies between two or more states, between a state and citizens of another state, between citizens of different states, between citizens of the same state, claiming lands under grants of different states, and between a state, or the citizens thereof, and foreign states, citizens or subjects." (Source: Article 3, Section 2, Paragraph 1) It further clarifies that "In all cases affecting ambassadors, other public ministers and consuls, and those in which a state shall be a party, the supreme court shall have original jurisdiction ... In all the other cases before mentioned, the supreme court shall have appellate jurisdiction, both as to law and fact, with such exceptions, and under such regulations as the Congress shall make." (Source: Article 3, Section 2, Paragraph 2) A later amendment also added that "The judicial power of the United States shall not be construed to extend to any suit in law or equity, commenced or prosecuted against one of the United States by citizens of another state, or by citizens or subjects of any foreign state." (Source: Eleventh Amendment, ratified 1795) Thus the Constitution clearly marked out the jurisdiction of the various courts in America. This would have an enormous effect on how trials were conducted in this country in that time and since.

"12 Angry Men" (1957), an American Hollywood movie dramatizing the "trial by jury" system

Right to trial by jury for criminal cases, and even for some civil cases

One of the most important guarantees of our liberties is the right of trial by jury. There was an explicit mention of this in the original Constitution, which said that "The trial of all crimes, except in cases of impeachment, shall be by jury; and such trial shall be held in the state where the said crimes shall have been committed; but when not committed within any state, the trial shall be at such place or places as the Congress may by law have directed." (Source: Article 3, Section 2, Paragraph 3) The Bill of Rights later expanded this with its famous Sixth Amendment, where it said that "In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the state and district wherein the crime shall have been committed; which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the assistance of counsel for his defence." (Source: Sixth Amendment) These rights are fairly easy for Americans to imagine, and they are fundamental to our protection as citizens. Thus, countless movies and TV shows have dramatized them time and time again in their depictions of the court system, and it is well that these rights are so well-known to Americans through these (and other) media. These rights are related to many fears about the arbitrary power of government (and the tyrannical exercise of that power). Trial by jury is thus available for some non-criminal offenses as well, such as how "In suits at common law, where the value in controversy shall exceed twenty dollars, the right of trial by jury shall be preserved, and no fact tried by a jury, shall be otherwise re-examined in any court of the United States, than according to the rules of the common law." (Source: Seventh Amendment) Thus the Constitution protects our rights when we are sued as well, and not just when we are accused of crimes.

United States Capitol, the seat of the United States Congress

Congress can't declare people guilty and punish them without a trial, or criminalize acts that were legal when they were done

The right of trial by the courts is also protected by another clause in the original Constitution, which said that "No bill of attainder or ex post facto law shall be passed." (Source: Article 1, Section 9, Paragraph 3) A "bill of attainder" is when a legislature (like the Congress) passes a law declaring a particular person or persons guilty of some crime, and even punishing them for this offense without a trial - something that only the courts have the power to do under American laws, when you have to give someone a fair trial first. This is necessary, in fact, before you can deny them any of the rights that they would otherwise have in this country. This is one of the bulwarks of our Constitution, since it is yet another protection of the right to a trial. Thus, even if one focuses here on the "Bill of Rights" and its protections, it would still nonetheless seem appropriate to mention here this "bill of attainder" clause from the original Constitution; which belongs to our discussion of the rights to a trial. (The "ex post facto" part, in case you're wondering, refers to laws against acts that were legal when committed, and so are declared illegal only after the fact - or in the Latin phrase, "ex post facto." It also refers to laws that increase the punishment for a crime after the fact, or laws which increase the seriousness of the offense after the fact. Finally, it refers to laws that change the rules of evidence after the fact to ensure easier convictions.)

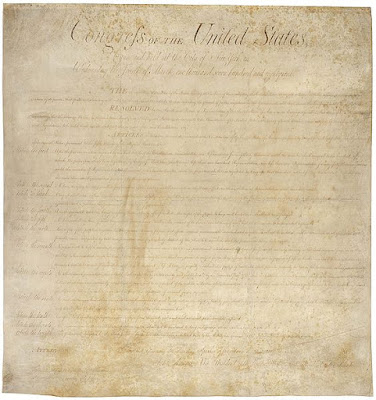

United States Bill of Rights

Police can't search people, confiscate things, or arrest people without the courts

The Bill of Rights says that "The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized." (Source: Fourth Amendment) Advocates of a "right to privacy" have long cited this part of the Constitution - which ironically authorizes some infringements of those rights when there is a warrant obtained from the court system authorizing the police to do it, by searching them or seizing their property. Nonetheless, it really does protect our right to privacy in most other circumstances. The original Constitution also said that "The privilege of the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in cases of rebellion or invasion the public safety may require it." (Source: Article 1, Section 9, Paragraph 2) The prohibition against suspending "habeas corpus" is actually another major check on the executive branch, since a "writ of habeas corpus" is a legal phrase for a document that allows accused persons who are unlawfully imprisoned (or otherwise detained) to petition the courts for a "speedy and public trial." It thus prohibits them from being detained indefinitely, when there is no trial to authorize this continued detention by an unfavorable verdict.

United States penitentiary on Alcatraz Island

Conclusion: An independent judiciary checks the power of the police

The Constitution thus set some very clear limits on the power of the police in this country, and on the power of the president that they report to. An executive branch with unlimited power to enforce the laws would be the worst sort of tyranny, since it would have an unlimited power to punish anyone that it pleased, without its victims having any sort of legal recourse to fight back. A police state like this would be unthinkable in America, because of the constitutional requirements for fair trials; and a separate judicial branch is thus one of the greatest defenses that a country can have against this. An independent judiciary with these vital checks on the executive branch - and its power to use deadly force against the people - keeps the power of judgment separate from the dreaded "power of the sword" in this country.

Footnote to this blog post:

Montesquieu once said that "Were the power of judging joined with the legislative, the life and liberty of the subject would be exposed to arbitrary control, for the judge would then be the legislator. Were it joined to the executive power, the judge might behave with all the violence of an oppressor." (Source: "The Spirit of Laws," Book XI, Chapter 6, as quoted by James Madison in Federalist No. 47)

This post continues here.

If you liked this post, you might also like:

Actually, the death penalty is constitutional (as the Fifth Amendment makes clear)

The Bill of Rights: Historical context and strict construction

The First Amendment: Protecting religion from government (and not the other way around)

The First Amendment: Protecting freedom of speech and freedom of the press

The Second Amendment: Protecting the gun rights "of the people"

Part of a series about

The Constitution

Introduction

Influences on the Constitution

Hobbes and Locke

Public and private property

Criticisms of social contract theory

Responses to the criticisms

Hypothesized influences

Magna Carta

Sir Edward Coke

Fundamental Orders of Connecticut

Massachusetts Body of Liberties

Sir William Blackstone

Virginia Declaration of Rights

The Declaration of Independence (1776)

Representative government

Polybius

Baron de Montesquieu

Articles of Confederation

The Constitution itself, and the story behind it

Convention at Philadelphia

States' rights

The Congress

Congress versus the president

Powers of Congress

Elected officials

Frequency of elections

Representation

Indigenous policies

Slavery

The presidency

Impeachment and removal

The courts

Amendment process

Debates over ratification

The "Federalist Papers"

Who is "Publius"?

Debates over checks & balances

The Bill of Rights

Policies on religion

Freedom of speech and press

Right to bear arms

Rights to fair trial

Rights of the accused

Congressional pay

Abolishing slavery

Backup plans

Voting rights

Epilogue

← Previous page: Right to bear arms - Next page: Rights of the accused →

No comments:

Post a Comment