“My intention here is not to exclude the consent of the people from being one just foundation of government where it has place. It is surely the best and most sacred of any. I only pretend, that it has very seldom had place in any degree, and never almost in its full extent. And that therefore some other foundation of government must also be admitted.”

– David Hume's “Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary” (1752), Part II, Essay XII (entitled “Of the Original Contract”)

Do governments require the “consent of the people”? If you think they do, you might be a believer in social contract theory, even if you don’t realize it yet. The idea that governments have actual duties to their people, and not just people having one-way duties to their governments, is at the foundation of every democracy; and is at the heart of social contract theory in every way.

United States Capitol

What is social contract theory, and why is it important?

In a nutshell, this social contract theory is basically the idea that there is an agreement between government and the people, which believers in this theory may or may not believe to have been written down on paper. In this agreement, it is held that governments agree to do certain things for their people, and that the people agree to do certain things for their society. These would include obeying the laws that their governments are actually authorized to make under this agreement – although not all laws would be authorized by these agreements, since some of these laws might be considered “unconstitutional” under its terms. (More on that later in this post – for now, I will just explain what social contract theory is at its most basic level.) What exactly the duties of each party might be is a matter of some controversy, I should acknowledge here, even among social contract theorists. Thus, I will not attempt here to specify numerous details of the duties owed by either side in this agreement. This would be too long a task for a single blog post, in fact, and would be beyond the scope of a blog like mine. Rather, I will attempt to show how social contract theory influenced the United States Constitution (since I am an American), and show how our own Constitution owes much to the English philosopher John Locke in this regard, since he was a great social contract theorist in a previous century. (For more on the basics of this theory, I will refer interested readers to another of my blog posts, which I link to here. This post will focus more on how this theory has been applied in actual practice, at least in my own country.)

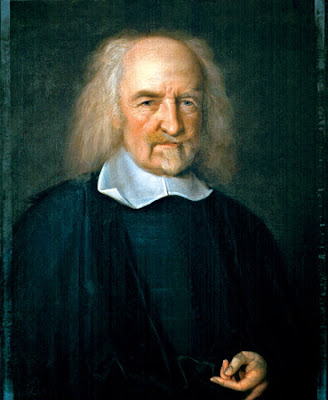

Thomas Hobbes

Like Hobbes, John Locke believed in the “state of nature” …

One of the key ideas of John Locke's “Second Treatise on Government” was that civil government was preceded by a “state of nature,” in which there was no government of any kind – an unpleasant situation that was opposed by both John Locke and Thomas Hobbes, the philosopher from whom Locke most directly got this idea. I will not spend much time discussing the state of nature here, since I have done so extensively in another blog post referenced earlier. The only reason that I refer to it now is to set up my discussion of the theory that is founded upon this concept – which is, of course, the “social contract theory.” In his “Second Treatise on Government,” John Locke commented that “I easily grant, that civil government is the proper remedy for the inconveniencies of the state of nature” (Source: Chapter II, Section 13).

John Locke

… and in social contract theory

John Locke also said that “every man, by consenting with others to make one body politic under one government, puts himself under an obligation, to every one of that society, to submit to the determination of the majority, and to be concluded by it; or else this original compact, whereby he with others incorporates into one society, would signify nothing, and be no compact, if he be left free, and under no other ties than he was in before in the state of nature.” (Source: Chapter VIII, Section 97) This is not to say that John Locke would have believed that there should be no limits upon the power of this majority, since even their power must be checked if minority rights are to be protected properly. (To assert that Locke believed this, as some may do, would be to take him out of context here; which is something that I have no desire to do.) Rather, it is to say that Locke held that majority rule was a general principle that was truly helpful for human society, and was even necessary to prevent abuses.

John Locke

This idea influenced James Madison (as quotations from the Federalist Papers show)

Locke was probably not the originator of social contract theory, I should acknowledge here, but he did modify it to make it consistent with democracy; which was a real innovation over the ideas of Thomas Hobbes. Like many other Founding Fathers, James Madison agreed with John Locke on this, and wrote in the Federalist Papers that “In a society under the forms of which the stronger faction can readily unite and oppress the weaker, anarchy may as truly be said to reign as in the state of nature, where the weaker individual is not secured against the violence of the stronger; and as, in the latter state, even the stronger individuals are prompted, by the uncertainty of their conditions, to submit to a government which may protect the weak as well as themselves; so, in the former state, will the more powerful factions or parties be gradually induced, by a like motive, to wish for a government which will protect all parties, the weaker as well as the more powerful.” (Source: Federalist No. 51) Thus the Constitution shows the influence of both the “state of nature” idea and the social contract idea.

James Madison

Locke believed that “all peaceful beginnings of government” came from consent of the people

In his “Second Treatise on Government,” John Locke actually wrote that “as far as we have any light from history, we have reason to conclude, that all peaceful beginnings of government have been laid in the consent of the people.” (Source: Chapter VIII, Section 112) One of the biggest criticisms of this idea was from the Scottish philosopher David Hume, whose influence on the Founding Fathers is less known than that of Locke or Montesquieu. (Although Hume was quoted by Alexander Hamilton in the last paragraph of the last essay of the Federalist Papers, on a subject relevant to the ratification debates. See the footnote to this blog post for the details of how David Hume was quoted there.) It was Hume's views on our current subject – namely, the social contract theory – that I will be quoting from in this part of this post.

Alexander Hamilton, who quoted David Hume in the closing paragraph of the Federalist Papers

David Hume was a critic of this historical account, and of social contract theory in general

In his “Essays, Moral, Political, Literary,” for example, David Hume wrote that “the contract, on which government is founded, is said to be the original contract; and consequently may be supposed too old to fall under the knowledge of the present generation. If the agreement, by which [primitive] men first associated and conjoined their force, be here meant, this is acknowledged to be real; but being so ancient, and being obliterated by a thousand changes of government and princes, it cannot now be supposed to retain any authority. If we would say any thing to the purpose, we must assert, that every particular government, which is lawful, and which imposes any duty of allegiance on the subject, was, at first, founded on consent and a voluntary compact. But besides that this supposes the consent of the fathers to bind the children, even to the most remote generations, (which republican writers will never allow) besides this, I say, it is not justified by history or experience, in any age or country of the world.” (Source: Part II, Essay XII – entitled “Of the Original Contract”)

David Hume

He believed that governments can be legitimate even without the beneficial “consent of the people” (although this would be the ultimate ideal for him)

Elsewhere in this part of his “Essays, Moral, Political, Literary,” David Hume wrote that “nothing is a clearer proof, that a theory of this kind is erroneous, than to find, that it leads to paradoxes, repugnant to the common sentiments of mankind, and to the practice and opinion of all nations and all ages. The doctrine, which founds all lawful government on an original contract, or consent of the people, is plainly of this kind; nor has the most noted of its partizans, in prosecution of it, scrupled to affirm, that absolute monarchy is inconsistent with civil society, and so can be no form of civil government at all; and that the supreme power in a state cannot take from any man, by taxes and impositions, any part of his property, without his own consent or that of his representatives.” (Source: Part II, Essay XII – entitled “Of the Original Contract”) Lest these Hume quotations be taken as a dismissal of the need for the “consent of the people,” I should note that elsewhere in this part of his “Essays, Moral, Political, Literary,” Hume wrote that “My intention here is not to exclude the consent of the people from being one just foundation of government where it has place. It is surely the best and most sacred of any. I only pretend, that it has very seldom had place in any degree, and never almost in its full extent. And that therefore some other foundation of government must also be admitted.” (Source: Part II, Essay XII – entitled “Of the Original Contract”) In short, virtually any government is better than none at all – according to Hume, at least – and a de facto government can be legitimate even without the consent that would ideally be present for it.

David Hume

Regardless of the historical origins of government, the Constitution is itself a social contract …

Some of Hume's criticisms of the theory of social contracts may be valid, and the idea that all governments actually began in this way is unsupported by the historical evidence, as Hume said. Many social contract theorists have agreed with this much, and have modified their theories accordingly to accommodate this criticism - saying that the “social contract theory” is still a workable model even without this claim that governments actually began in this way. But regardless of the actual historical origins of government (which I have discussed earlier), one might note with some satisfaction that some “social contracts” really have been enacted between government and the people, and that the Constitution itself was one of these “social contracts” (even if it was after Hume’s time, which it was).

Constitutional Convention, 1787

… as our next post will show

People agreed to obey the laws by creating a government that had the power to make them, and which had the power to punish violations of those laws via particular clauses in the document. In return, the government agreed to stay within the bounds prescribed by the Constitution, and to consider itself in violation of these laws anytime that it got out of bounds anyway. (More on that subject in our next post in this series.)

Footnote to this blog post:

In 1788, Americans would debate fiercely about whether or not we should adopt the “proposed Constitution” that had just been drafted in Philadelphia. The document that we now have as our Constitution was not a popular one at this time, and its opponents threw many charges at it to make a case that it was “fundamentally flawed” (in the language they might have used at this time).

I think “fundamentally flawed” may be stretching it a bit (to put it mildly), but it is true that Alexander Hamilton did not believe the document was perfect. On the contrary, he believed it was not perfect, even if it was a step in the right direction. Moreover, he knew that it was perceived as less-than-perfect by many Americans; and so he quoted from David Hume in the last paragraph of the Federalist Papers. The quote from Mr. Hume was as follows:

“To balance a large state or society … whether monarchical or republican, on general laws, is a work of so great difficulty, that no human genius, however comprehensive, is able, by the mere dint of reason and reflection, to effect it. The judgments of many must unite in the work; experience must guide their labor; time must bring it to perfection, and the feeling of inconveniences must correct the mistakes which they INEVITABLY fall into in their first trials and experiments.” (Source: Hume's “Essays, Moral, Political, Literary,” Part I, Essay XIV, entitled "Of the Rise and Progress of the Arts and Sciences" - as quoted by Hamilton in Federalist No. 85)

Thus, we cannot expect perfection from “general laws,” and the Constitution should not be held to impossibly high standards that no one can ever meet.

If you liked this post, you might also like:

How David Hume influenced “The Wealth of Nations”

The basics of the “state of nature” and the social contract

How Locke influenced the Declaration of Independence

In defense of John Locke: The need for private property

How did the United States Constitution apply social contract theory?

Part of a series about the

U. S. Constitution

Introduction

Influences on the Constitution

Hobbes and Locke

Public and private property

Criticisms of social contract theory

Responses to the criticisms

Hypothesized influences

Magna Carta

Sir Edward Coke

Fundamental Orders of Connecticut

Massachusetts Body of Liberties

Sir William Blackstone

Virginia Declaration of Rights

The Declaration of Independence (1776)

Representative government

Polybius

Baron de Montesquieu

Articles of Confederation

The Constitution itself, and the story behind it

Convention at Philadelphia

States' rights

The Congress

Congress versus the president

Powers of Congress

Elected officials

Frequency of elections

Representation

Indigenous policies

Slavery

The presidency

Impeachment and removal

The courts

Amendment process

Debates over ratification

The "Federalist Papers"

Who is "Publius"?

Debates over checks & balances

The Bill of Rights

Policies on religion

Freedom of speech and press

Right to bear arms

Rights to fair trial

Rights of the accused

Congressional pay

Abolishing slavery

Backup plans

Voting rights

Epilogue

← Previous page: Public and private property – Next page: Responses to the criticisms →

No comments:

Post a Comment