“We, therefore, the people of Massachusetts, acknowledging, with grateful hearts, the goodness of the great Legislator of the universe, in affording us, in the course of His providence, an opportunity, deliberately and peaceably, without fraud, violence or surprise, of entering into an original, explicit, and solemn compact with each other; and of forming a new constitution of civil government, for ourselves and posterity; and devoutly imploring His direction in so interesting a design, do agree upon, ordain and establish the following Declaration of Rights, and Frame of Government, as the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.”

The Constitution of Massachusetts was originally written by John Adams …

In 1787, John Adams was serving as the American ambassador to Britain. Thus, he was not present at the (federal) Constitutional Convention, which was held that year. But he had more influence upon the federal Constitution than one might be tempted to conclude from this. This is because, eight years earlier, he had attended the Massachusetts Constitutional Convention held in 1779. Thus, he was the principal author of the Constitution of Massachusetts. This is among the oldest written constitutions to remain in effect today. It was also the first constitution anywhere in the world to be “created by a convention called for that purpose, rather than by a legislative body” (as one source puts it).

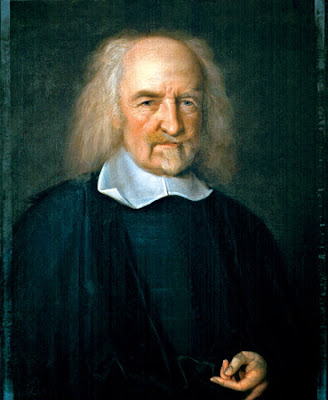

John Adams, the principal author of the Constitution of Massachusetts

… and remained unchanged until the 1820s, long after the founding era

This constitution remained unchanged until the Second Massachusetts Constitutional Convention. This latter convention was held from 1820 to 1821. At this time, the first nine amendments to the Massachusetts Constitution were all passed simultaneously. Thus, all of the amendments to that constitution were well after the founding era. I will be focusing here on how the Massachusetts Constitution influenced the federal Constitution. Thus, all of the amendments to the Massachusetts Constitution (even the very first one) are too late to be relevant to our present subject. Thus, I will be focusing here on the original text of the Massachusetts Constitution – as drafted in 1779, and presented and ratified in 1780. This will showcase the ideas of John Adams, and how they influenced our federal Constitution.

The title page of the first published edition of the original 1780 Massachusetts Constitution