"Posterity! You will never know, how much it cost the present generation, to preserve your freedom! I hope you will make a good use of it. If you do not, I shall repent in heaven, that I ever took half the pains to preserve it."

- John Adams, in a letter to his wife Abigail Adams (26 April 1777)

He was a powerful leader, who stood only five feet six inches tall. He was popular enough to be elected president, but considered himself an obnoxious man, with a brashness that could alienate even his friends. And he was one of our greatest presidents, but was only elected to one term, passed over in favor of an old friend.

Young John Adams

His name was John Adams, and he was one of this country's Founding Fathers. He had many significant accomplishments in his life, but the greatest of them was his central role in the Declaration of Independence. Even his presidency was not as important as this. He was on the Committee of Five assigned to write the Declaration of Independence, but he did not want to write the document, preferring that it instead be written by Thomas Jefferson. Why, then, is he remembered as such a central figure in the document's history? Mainly, it is two things. One is that he was the one who convinced Thomas Jefferson to write the Declaration, and the other is that he was the principal force behind getting it passed. Jefferson was the one who wrote it, but Adams was the one who convinced the Continental Congress to sign it; thus risking their own lives in an act of revolution punishable by death. We could easily have lost that war, and every signer of that document could have been hanged as a traitor. But despite their knowing the risks, they all took the risk (save John Dickinson), largely due to the powerful leadership of John Adams.

John Trumbull's Declaration of Independence

He possessed a gift for oratory which manifested itself very early in his career, when he was a trial lawyer in colonial Boston. Despite his disapproval of the crown's occupation of Boston, he defended the soldiers accused in the so-called "Boston Massacre," and got most of them off in a stunning acquittal. He had no love of King George the Third; but he distrusted mobs, considering them an enemy of peace and order; and managed to get the unpopular soldiers acquitted of murder charges - an event dramatized in the HBO miniseries about his life, but almost omitted in the miniseries "The Adams Chronicles." ("The Adams Chronicles," though, has the virtue of depicting his early life - and his courtship of Abigail Adams - which is entirely omitted in HBO's miniseries.) The rhetorical skill manifested in the "Boston Massacre" trial allowed him to take part in debates on the floor of Congress, using a great skill in oratory that was lacked by Thomas Jefferson. (Jefferson was a powerful writer, but he himself admitted that he had no gift for oratory; and thus could not have led the fight in Congress the way Adams did.)

Abigail Adams, wife

George Washington

Adams nominated George Washington to serve as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, which must have served him well when Washington later sought his advice as president. Soon after the Declaration of Independence was made, though, he was sent on a diplomatic mission to France, to convince the only superpower in the world (besides their British enemy) to back the American cause. But the qualities that had served him so well in Congress - leadership, debating skill, and rhetorical power - were of no use to him in France, and he was a terrible diplomat. Benjamin Franklin - the other ambassador - actually asked the Congress to have Adams removed as ambassador, because Adams' tactless ways and open hostility to the French were obstructing the important diplomacy with this massive superpower. Adams was sent to the Netherlands instead, where his diplomacy fared somewhat better; and he was later returned to France near the time that the peace treaty was going to be signed.

Benjamin Franklin as ambassador to France

Adams' declarations of hostility to the French had been tactless and counter-productive; but he was right to mistrust and suspect the French. Thus, he convinced Benjamin Franklin to make a separate peace with Britain, cutting the French out of the peace negotiations. This was in violation of the Treaty of Alliance with France, something both men well knew; but America was no longer bound by these obligations, as France had backed out on her end of the deal. Specifically, France had expressed a willingness to negotiate away American independence, to get other things that they wanted from Britain. Thus, Benjamin Franklin went along with Adams' plan, getting the recognition of American independence from Britain (which would otherwise not have been given). He also later smoothed things over with the French, with a letter that has become a classic of diplomatic history. (Only Franklin, the smooth operator extraordinaire, could have smoothed things over so well.) All of the television biographies I've seen of John Adams have omitted his important role in the peace treaty with Britain; but it is covered in some detail in PBS's Benjamin Franklin documentary, where they show Adams redeeming himself for his tactless diplomacy of earlier years.

The Constitutional Convention

Adams missed the Constitutional Convention because of being postwar ambassador to Britain; an unenviable post where his tough (and sometimes hostile) nature was more appropriately used, because of the lingering hostility between the former enemies. (No need for pretense of phony sentiment, as the two sides remained openly hostile.) He returned home to be elected vice president under George Washington, with his advice sometimes sought in Cabinet meetings; but he was ill-suited to the role of vice president, where he was unable to lead anything, and had to play second fiddle to George Washington. The vice presidency made him President of the Senate, but prevented him from casting any votes unless there was a tie; and the Senate also prohibited him from speaking, and taking part in debates. Surely, this was a grave punishment for a man who loved to talk so much.

Naval engagement in the "Quasi-War"

His presidency, though, was a generally successful one, where he continued the Washington administration's policy of trying to keep America neutral in the war between Britain and France, the two great superpowers of that time. This was not an easy task, given the French willingness to fight Americans on the high seas. This undeclared naval war is sometimes labeled today the "Quasi-War," and it was the single greatest issue in Adams' presidency. But Adams prevented it from escalating into a full-scale war, and made peace with France as soon as Napoleon came into power. Unfortunately, the news of the peace came too late to prevent his defeat in the election of 1800; and the country thus soon elected his former friend Thomas Jefferson, with whom he was no longer on speaking terms. The two men did not speak for years after. Incidentally, John Adams was the first of the presidents to be affiliated with a political party. He was also our only president from the Federalist Party, a party that has since dissolved.

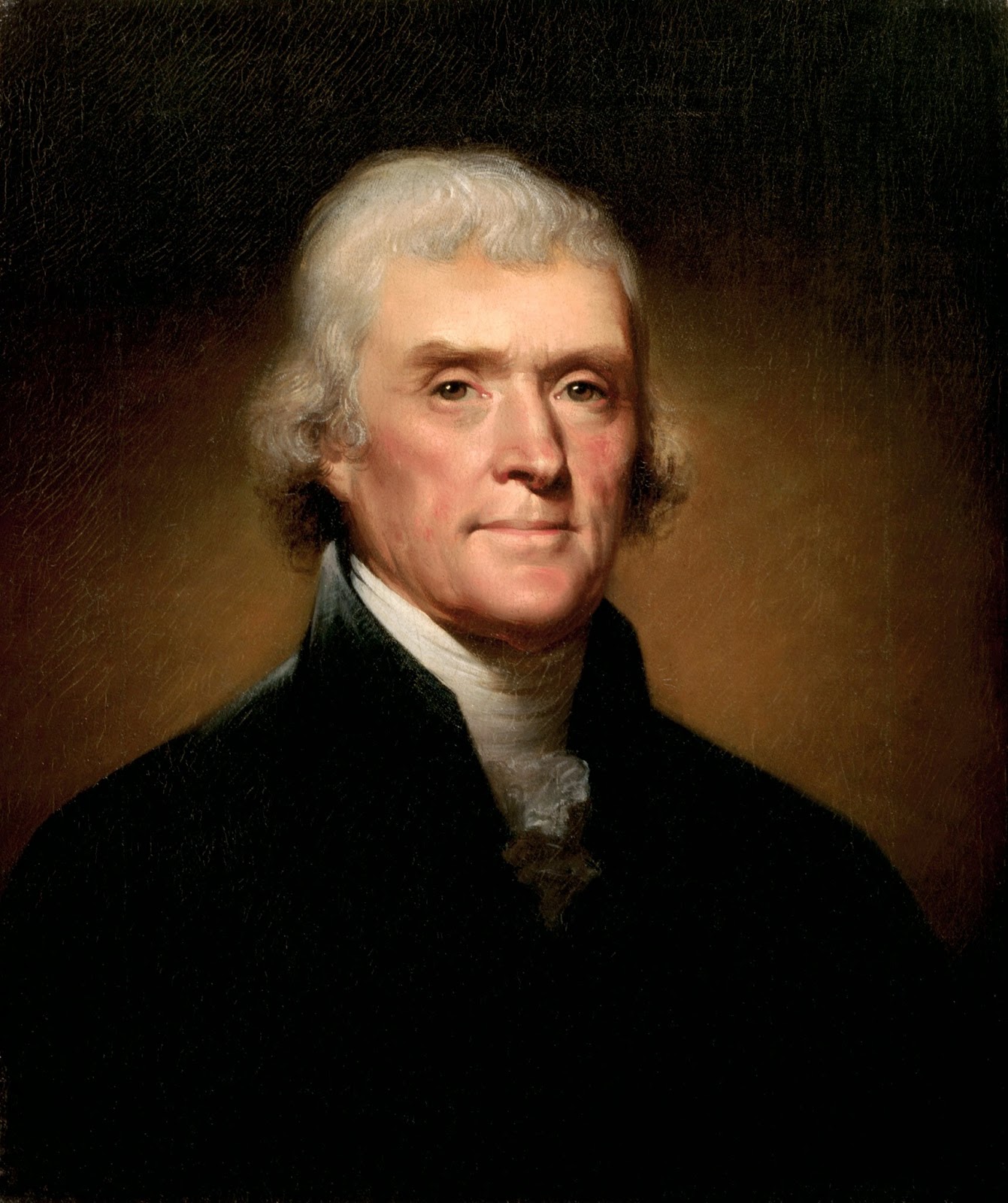

Thomas Jefferson

But a mutual friend and fellow signer of the Declaration of Independence, Dr. Benjamin Rush, convinced John Adams to break the silence; and begin corresponding with his former friend Thomas Jefferson. The two men wrote a series of letters, in which they reconciled and talked to each other as the best of friends. Their letters are charming and witty, and among the great treasures of American literature. Near the end of their lives, the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence was approaching, and Thomas Jefferson wanted to live to see it. He kept asking on his deathbed: "Is it the Fourth? Is it the Fourth?" He actually passed away on that fiftieth anniversary, to be followed hours later by John Adams ... on that same day! Adams' last words were "Thomas Jefferson survives" - and in the words of one documentary, he was "wrong for the moment, but right for the ages." This is among the most astonishing coincidences in American history - strong enough to make you suspect divine design in the matter. In the words of PBS's documentary about John Adams (linked to below), it was "more poetry than history" - although it was certainly history as well.

Older John Adams

So that's a little about why I find John Adams so interesting. I will not compare and contrast these three films about him, for this blog post is already long enough; but I link to another blog post where I do so, for those who are interested in viewing them.

"[T]he great anniversary festival [Independence Day] ... ought to be commemorated as the day of deliverance, by solemn acts of devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires, and illuminations, from one end of this continent to the other, from this time forward, forevermore.

"You will think me transported with enthusiasm, but I am not. I am well aware of the toil and blood and treasure that it will cost us to maintain this Declaration, and support and defend these States. Yet through all the gloom I can see the rays of ravishing light and glory. I can see that the end is more than worth all the means; and that posterity will triumph in that day' s transaction, even although we should rue it, which I trust in God we shall not."

- John Adams, in a letter to his wife Abigail Adams, 3 July 1776

If you liked this post, you might also like:

John Adams movies

A review of Ken Burns' "Benjamin Franklin" (PBS)

A review of Ken Burns' "Thomas Jefferson" (PBS)

A review of "Lafayette: The Lost Hero" (PBS)

In defense of the American Founding Fathers

John Quincy Adams: A great statesman in his own right

PBS documentary is

Available on YouTube

(see below)

Part of a series about

The Founding Fathers

Benjamin Franklin

George Washington

Alexander Hamilton

John Adams

Thomas Jefferson

James Madison

Part of a series about

The Presidents

1. George Washington

2. John Adams

3. Thomas Jefferson

4. James Madison

5. James Monroe

6. John Quincy Adams

7. Andrew Jackson

8. Martin Van Buren

15. James Buchanan

16. Abraham Lincoln

17. Andrew Johnson

18. Ulysses S. Grant

19. Rutherford B. Hayes

20. James A. Garfield

25. William McKinley

26. Theodore Roosevelt

27. William Howard Taft

28. Woodrow Wilson

31. Herbert Hoover

32. Franklin Delano Roosevelt

33. Harry S. Truman

34. Dwight D. Eisenhower

35. John F. Kennedy

36. Lyndon B. Johnson

37. Richard Nixon

38. Gerald Ford

39. Jimmy Carter

40. Ronald Reagan

41. George H. W. Bush

42. Bill Clinton

43. George W. Bush

44. Barack Obama

46. Joe Biden

2. John Adams

3. Thomas Jefferson

4. James Madison

5. James Monroe

6. John Quincy Adams

7. Andrew Jackson

8. Martin Van Buren

15. James Buchanan

16. Abraham Lincoln

17. Andrew Johnson

18. Ulysses S. Grant

19. Rutherford B. Hayes

20. James A. Garfield

25. William McKinley

26. Theodore Roosevelt

27. William Howard Taft

28. Woodrow Wilson

31. Herbert Hoover

32. Franklin Delano Roosevelt

33. Harry S. Truman

34. Dwight D. Eisenhower

35. John F. Kennedy

36. Lyndon B. Johnson

37. Richard Nixon

38. Gerald Ford

39. Jimmy Carter

40. Ronald Reagan

41. George H. W. Bush

42. Bill Clinton

43. George W. Bush

44. Barack Obama

46. Joe Biden

No comments:

Post a Comment