"The ratification of the conventions of nine states, shall be sufficient for the establishment of this constitution between the states so ratifying the same."

- Article 7 of the United States Constitution

The Constitutional Convention

Our national debate over the Constitution is as old as the Constitution itself, with origins to be found in the events of the Constitutional Convention, where its particulars were first debated by the men present at the convention. The framers of the Constitution disagreed with each other vehemently on exactly what the document should say and do, and how it should say and do it. Moreover, a number of the men present at the convention refused to even sign the document after the debates at the convention. As many of them well knew, though, the national debate over what they had written was just beginning. With the strict secrecy of the convention's proceedings at the time that it was still going on, the nation didn't know what was in the document until after the finished product of the convention was presented to the nation. Many of them weren't all that happy over the things they found in it, to put it mildly.

A replica of Independence Hall, which is not surrounded by

high-rise buildings (that don't belong in the period) the way the real one is today

high-rise buildings (that don't belong in the period) the way the real one is today

Why did so many people suspect the Constitution was "dangerous"?

Part of this may have been that they got all their surprises about the document at virtually the same time. They had not been witness to the deals and compromises that had taken place so gradually during the events of the convention. A gradual revelation of the document's contents thus was simply not possible after the nation's curiosity had been whetted by the "secrecy rule." (Which is not a criticism of the "secrecy rule," I should make clear; but it was only natural for the people to wonder about it. Many of them assumed that the convention had something to hide in this regard, after the secret proceedings had been continuing for some four months without news.) The supporters of the Constitution all knew that they faced an uphill battle when they presented the final document to the people. This uphill battle is today known as the debates over ratification (or the ratification debates) - arguably the most important debates in the nation's history, because of the sheer number of issues that it affected, then and now. If I might point this out, it affected the very same democratic process by which all future political issues would be debated in America - and by extension, in a number of other places as well.

Newspaper advertisement for the Federalist Papers, 1787 (a part of the ratification debates)

The alternative: Depending on "accident and force"

Alexander Hamilton asks rhetorically in the first of the Federalist Papers "whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice" (as they were called upon to do in the ratification debates), or "whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force" (Source: Federalist No. 1). This was a frightening alternative that was a real possibility at that point. "Reflection and choice" is a good description of how the country acted next, in deciding whether or not to ratify the document. Even the most zealous of the Constitution's supporters did not expect this to be accomplished overnight. The Constitution was a revolutionary document with many far-reaching effects on the future history of the United States. Thus, the country had good reason to think about it carefully - and examine every aspect of it in painstaking detail - before deciding whether or not to adopt it as the "supreme law of the land" on a permanent basis, as they were called upon to do. They'd only known about the Constitution for a comparatively short while, after all; and they needed some time to get used to this new idea before giving their permanent stamp of approval to it (which could be perpetual).

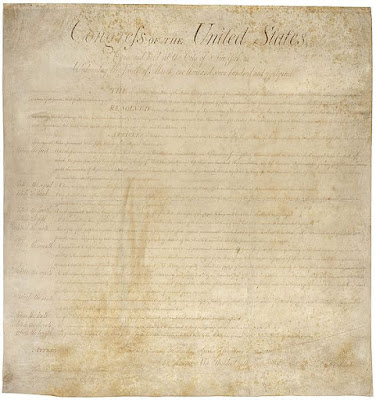

The Constitution

The charge that the Constitution was "illegal"

The part of the Constitution that may have had the greatest influence on these debates was the one that actually broke some prior laws, which was Article 7. Specifically, it said that "The ratification of the conventions of nine states, shall be sufficient for the establishment of this constitution between the states so ratifying the same." The significance of this passage came from its only requiring "nine" states (rather than all thirteen) to put the document into effect. The reason that this broke some prior laws was because the document it replaced - the "Articles of Confederation," to be specific - had a part of it saying that "nor shall any alteration at any time hereafter be made" to the existing system of government, "unless such alteration be agreed to in a Congress of the United States, and be afterwards confirmed by the legislatures of every state" (Source: Article XIII). Thus, total unanimity was required under the prior laws to do anything like pass a new Constitution. Instructions to the delegates of the Constitutional Convention specifically forbade many of them from doing so. This not only affected the rules of the game for what was needed to pass the Constitution, but also ignited a fierce procedural debate over whether the country as a whole had a right to adopt this Constitution, without the unanimity required by these prior laws. This debate was more than merely theoretical, given that the state of Rhode Island had refused even to send delegates to the Constitutional Convention, and was sure to try and boycott the debates over ratification as well. This made the unanimity required by these prior laws virtually impossible to get in practice (perhaps absolutely impossible). Thus, the Constitution simply wasn't going to get passed, if the "unanimity rule" was followed here.

James Madison

John Trumbull's Declaration of Independence

Responses to the illegality charge

James Madison later responded to the charge of illegality in the Federalist Papers, by quoting - or rather, paraphrasing - from the Declaration of Independence itself. The relevant paraphrase said that the people could "abolish or alter their governments as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness" - something which would not have been possible under a strict adherence to prior laws. (Source: Madison's paraphrase in Federalist No. 40) He thus compared violating prior laws to pass the Constitution, to the colonies' decision to break the laws of the mother country (Great Britain) in declaring their independence from it to begin with. This is a claim so loaded, and so revolutionary, that it's almost impossible to overstate just how significant it was at that time, given the dire straits that the colonies were in, from having a government so weak as the one of that time. The Constitution, in other words, was a Second American Revolution. Moreover, the situation was so desperate - and so similar to the one faced by the colonists, when rebelling against King George the Third - that the states were justified in breaking the laws to pass this Constitution, just as they had been in rebelling against the British and establishing their own country to begin with. (And lest this point not be understood, let me say explicitly that this was all true - it really was that desperate. The union was about ready to fracture if the new Constitution was not passed; and the thirteen states were in very real danger of anarchy, bankruptcy, and even civil war. This is why there was a Constitutional Convention to begin with.)

Interior of Independence Hall

Pro-Constitution strategy of speed

Perhaps partly because of this, the supporters of the Constitution decided on a strategy of speed in getting the Constitution passed, so that the opponents of ratification might not kill it through excessive delay and prolonged debates. Some amount of debate was reasonable (and even necessary) for a plan as extensive and far-reaching as the "proposed Constitution," and the people needed time to inspect it thoroughly. Nonetheless, too much would have been a catastrophe, as it would have made the public standards of acceptability so unreasonable as to be impossible to meet. At some point, the people needed to make up their minds. So the debate was fought in one state after another, as each state debated the merits of the Constitution piece-by-piece, and (in some cases) clause-by-clause. Some issues were unique to particular states, while others were debated in virtually every state. But the consistent thing about these debates is that they were prolonged, and that they were intense - with both sides growing tired of hearing the others' arguments, after this had been going on for some time. The debates actually dragged on for months, which was the degree of "reflection and choice" that the people were willing to give it. They did indeed "establish good government" by reflection and choice, as Alexander Hamilton had predicted.

Alexander Hamilton

The issues they debated about

Time does not permit anything but a brief overview of the issues they debated about, but suffice it to mention a few examples which would be difficult to leave out of this post. One was the taxing power of the Congress, which the Constitution's opponents found dangerously unlimited. Another was the issue of slavery, which was addressed in the Constitution in a way that the Southern slaveholders found mostly satisfactory, but which drew the ire of many Northern states (and understandably so), as it gave constitutional power to the institution of slavery. Another was the power of the "executive branch" (or the presidency), with the very idea of executive power being strongly suspected in eighteenth-century America. It was so strongly suspected, in fact, that the Constitution's predecessor had not included any executive branch at all - just a Congress with limited power. Still another was the "necessary and proper" clause, which gave the Congress the power to make all laws which shall be "necessary and proper" for putting the Constitution's passages into effect (Source: Article 1, Section 8, Paragraph 18) - something that the Constitution's opponents saw as dangerously vague about how much power was granted. (Even some notable Founding Fathers - notably, Patrick Henry - made arguments of this kind against the Constitution.)

Patrick Henry

The "bill of rights": The most important issue

But the issue which drew its opponents' fire the most - and the one that those opponents would eventually win on - is the Constitution's lack of a "bill of rights." This was the only real concession that the Constitution's opponents actually got, although it was a very important one. Some states actually considered refusing to ratify the Constitution, unless they first came up with a bill of rights that was sufficiently satisfactory. Many states that did ratify the Constitution actually sent recommendations about what to include in it, along with the completed documents for ratification. This tactic drew the ire of the Constitution's opponents, because they advocated making ratification conditional upon getting the needed concessions up front. This delaying tactic might have succeeded in stopping the Constitution, if it had been allowed to be implemented. (But that's a topic for another post.) They essentially made the argument that ratifying the Constitution before these changes were made, on the strength of political promises to "do so later," was inherently dangerous (and thus unacceptable). There may have been some truth in this, depending on your point of view; but fortunately, the pro-Constitution side lived up to its reluctant promises to include one afterward, and so the country was better off as a result. All things considered, things worked out as they should have. Thus, the country was spared from the kind of tyrannical government that might have followed a Constitution without a bill of rights - a danger that the Constitution's opponents can accurately say they prevented through their steadfast efforts on this issue. (Not all of the opposition to the Constitution was misguided, as the document's critics of that time had some real points to make - much more, I think, than the document's critics have today.)

United States Bill of Rights

Conclusion: We actually owe our freedom to both sides (and here's why)

In the end, the country got both an improved constitution and a national bill of rights. Thus, each side could claim some accomplishments in the victories that it had gained. Even their defeats were actually victories for the American people in the long run, and we can well be glad that the ratification debates turned out as they did. We live today in a society with a free system of government created by the one side, and basic human rights protected by the other - with the compromises actually turning out better than total victory for either side would have done. In a very real sense, it can be said that we owe our freedoms to them both, and that each side had much of value to contribute to the democracy we live in today.

Footnote to this blog post:

In the very opening lines of the Federalist Papers, Alexander Hamilton wrote that "After an unequivocal experience of the insufficiency of the subsisting federal government, you are called upon to deliberate on a new Constitution for the United States of America. The subject speaks its own importance; comprehending in its consequences nothing less than the existence of the UNION, the safety and welfare of the parts of which it is composed, the fate of an empire in many respects the most interesting in the world." (Source: Federalist No. 1)

If you liked this post, you might also like:

How different was the Constitution from the "Articles of Confederation"?

The Constitutional Convention: A notable movie about these events

The "who, what, when, where, how, why" of the Federalist Papers

"Publius": The secret pen name of three Founding Fathers

The Bill of Rights: Historical context and strict construction

In defense of the American Founding Fathers

Part of a series about

Political philosophy

The Ratification Debates

Others to be covered later

Part of another series about

The Constitution

Introduction

Influences on the Constitution

Hobbes and Locke

Public and private property

Criticisms of social contract theory

Responses to the criticisms

Hypothesized influences

Magna Carta

Sir Edward Coke

Fundamental Orders of Connecticut

Massachusetts Body of Liberties

Sir William Blackstone

Virginia Declaration of Rights

The Declaration of Independence (1776)

Representative government

Polybius

Baron de Montesquieu

Articles of Confederation

The Constitution itself, and the story behind it

Convention at Philadelphia

States' rights

The Congress

Congress versus the president

Powers of Congress

Elected officials

Frequency of elections

Representation

Indigenous policies

Slavery

The presidency

Impeachment and removal

The courts

Amendment process

Debates over ratification

The "Federalist Papers"

Who is "Publius"?

Debates over checks & balances

The Bill of Rights

Policies on religion

Freedom of speech and press

Right to bear arms

Rights to fair trial

Rights of the accused

Congressional pay

Abolishing slavery

Backup plans

Voting rights

Epilogue

← Previous page: Miscellaneous (Amendment Process etc.) - Next page: The "Federalist Papers" →

Part of a series about

American history

The Ratification Debates

No comments:

Post a Comment