“In the most pure democracies of Greece, many of the executive functions were performed, not by the people themselves, but by officers elected by the people, and REPRESENTING the people in their EXECUTIVE capacity … Prior to the reform of Solon, Athens was governed by nine Archons, annually ELECTED BY THE PEOPLE AT LARGE. The degree of power delegated to them seems to be left in great obscurity. Subsequent to that period, we find an assembly, first of four, and afterwards of six hundred members, annually ELECTED BY THE PEOPLE; and PARTIALLY representing them in their LEGISLATIVE capacity, since they were not only associated with the people in the function of making laws, but had the exclusive right of originating legislative propositions to the people.”

Western culture now seems to be falling out of fashion today. People understandably want to praise the other cultures of the world, and note that they made significant contributions to the arts, sciences, and philosophy. They thus feel that we somehow have to downgrade the contributions of the West. They seem to feel that elevating other cultures requires us to knock Western culture off of its pedestal – a problematic proposition. The legacy of the Ancient Greeks and Romans is one of the casualties of this problematic way of thinking. The Ancient Greeks and Romans may have been “great,” say others, but they were just two cultures among many – and they were no more “great” than any other cultures, says this group. They may have been “special,” this group admits, but all cultures are “special” – depriving this word of any real meaning.

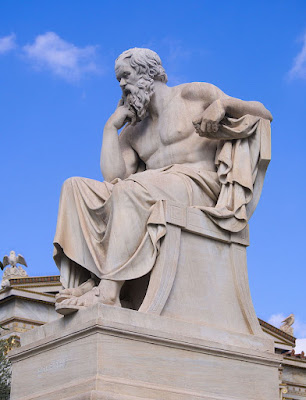

The Pnyx in Greece, the meeting place of the people of Athens

So what did the Ancient Greeks and Romans really leave us, you might be wondering? Oh, nothing much: just democracy … and maybe a few other important things. This post will try to explain why the Ancient Greeks and Romans were different. I should note that, to my knowledge, I don’t have a single drop of Greek or Italian blood in me. Thus, to me, this is not about genetics or “privileged bloodlines.” Rather, I see this as being about ideas – with freedom, possibly, being the very greatest of those classical ideas. By creating popular government, the Ancient Greeks and Romans both left us a legacy of free inquiry and pursuit of truth. To me, that is their greatest legacy. It needs to be remembered today, and it needs to be reverently (and thoughtfully) taught today.

The “Forum Romanum,” better known as the Roman Forum