It might seem strange to say it today, but the “Bill of Rights” amendments were once understood to apply only to the federal government, rather than to the states as well. This was a particular problem when you consider that the states had (at times) denied these protections to African Americans (and others), even after the abolition of slavery by the Thirteenth Amendment.

First page of the Fourteenth Amendment

Section 1: All persons “born or naturalized” in the United States are citizens …

Thus, the Fourteenth Amendment (ratified in 1868) later applied the Bill of Rights to the states as well. (This was three years after the Civil War.) The Fourteenth Amendment first prefaced this application by clarifying that “All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.” (Source: Section 1 of the amendment) Thus, they clarified that African Americans who had been “born ... in the United States” were citizens under the law. I should also clarify that “naturaliz[ation]” is just a word that means “becoming a citizen.” With this in mind, the original Constitution had said that the federal Congress shall have the power to “establish an uniform rule of naturalization” (Source: Article 1, Section 8, Paragraph 4). This put the creation of immigration laws under federal control. Another reason that I mention this is to transition into discussing another major part of the Fourteenth Amendment, which is related to this.

United States Bill of Rights

… and the states have to respect the rights of their citizens

With these clarifications in mind, I will now quote the part of the Fourteenth Amendment that applies the Bill of Rights to the states: “No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” (Source: Section 1 of the amendment) The phrase about “depriv[ing] any person of life” is an explicit reference to the death penalty, which authorizes capital punishment by the states when there is indeed “due process of law.” But most controversies regarding this section have actually revolved around the phrase “equal protection of the laws.” What does this mean, specifically? Legal scholars continue to debate this today, and the debate is not without some applications. A number of “protections” are at stake in how this is defined.

Frederick Douglass, a staunch supporter of the Fourteenth Amendment

The Three-Fifths Clause was replaced by Section 2, which had some new rules about representation …

In the original Constitution, there was an infamous provision known as the “Three-Fifths Clause.” (More about that here.) This clause is as follows: “Representatives and direct taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole number of free persons, including those bound to service for a term of years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three-fifths of all other persons.” (Source: Article 1, Section 2, Paragraph 3) This effectively rewarded the Southern states for practicing slavery, with the added representation in Congress being proportioned to three-fifths of their slave populations. Ironically, it was the Southerners who would have liked this number to be higher, so that their states could have additional votes that only their white populations controlled. Slaves could not vote at this time, and thus were unable to control any of the power that their presence brought to the state. The real control at this time was in the hands of whites.

The Constitutional Convention, 1787

… some of which were actually sexist, although they have since been modified

With this in mind, the Fourteenth Amendment said that: “Representatives shall be apportioned among the several States according to their respective numbers, counting the whole number of persons in each State, excluding Indians not taxed. But when the right to vote at any election for the choice of Electors for President and Vice-President of the United States, Representatives in Congress, the executive and judicial officers of a State, or the members of the legislature thereof, is denied to any of the male inhabitants of such State, being twenty-one years of age, and citizens of the United States, or in any way abridged, except for participation in rebellion, or other crime, the basis of representation therein shall be reduced in the proportion which the number of such male citizens shall bear to the whole number of male citizens twenty-one years of age in such State.” (Source: Section 2 of the amendment) In other words, this amendment said, the Southern states don't get the full added votes if African American males in it are still being denied a say in it. The fact that this provision only applied to males was undoubtedly a major weakness, and one which set back the women's rights movement for decades (the aforementioned “sexism” of this section of the amendment). But it was nonetheless an attempt to provide for the punishment of any states that denied voting rights to their former slaves. It would have been fortunate indeed if this provision had actually been enforced during the segregation era following the Civil War, when voting rights were nonetheless denied to many African Americans on account of their race. (With the exception of certain parts of the Reconstruction Era, African Americans did not often receive voting rights until the civil rights movement of the 1960's.) However, white Southerners could actually be denied the right to vote “for participation in rebellion, or other crime” – and this was sometimes done at this time. Incidentally, another part of the Three-Fifths Clause was later repealed by another amendment in 1913. The Sixteenth Amendment later said that the Congress could lay and collect taxes on incomes “without apportionment among the several States, and without regard to any census or enumeration.” (Source: Sixteenth Amendment) Thus, taxation is no longer proportioned to population, although representation in the House of Representatives still is.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, two vocal opponents of the Fourteenth Amendment

Section 3: Former Confederates could be barred from holding office, at least for a time …

The original Constitution had said that “The senators and representatives before-mentioned, and the members of the several state legislatures, and all executive and judicial officers, both of the United States and of the several states, shall be bound by oath or affirmation, to support this constitution; but no religious test shall ever be required as a qualification to any office or public trust under the United States.” (Source: Article 6, Section 3) With this in mind, the Fourteenth Amendment added that “No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or Elector of President and Vice-President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State Legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.” (Source: Section 3 of the amendment) Some commentary on this section would seem appropriate here.

Jefferson Davis, the only president of the Confederacy

… and so can others who have committed treason against their oaths to the Constitution

When the Fourteenth Amendment was first passed in 1868 (after the Civil War), this section's immediate purpose was to bar former Confederates from holding office; at least for a time. Congress did indeed, “by a two-thirds vote of each House, remove such disability” for many former Confederates later on; but not for all of them. Some, like the former Confederate president Jefferson Davis, continued to be barred for life; and I know of at least one case where someone besides a former Confederate was thus barred. In 1919 and 1920, for example, Socialist Victor L. Berger, who was convicted of violating the Espionage Act for publishing his anti-militarist views during World War One, was prevented from taking his seat in the House of Representatives under this section. I should note, however, that this verdict was later overturned by the Supreme Court; so Mr. Berger was thus elected to three successive terms after this in the 1920's. Lest this be construed as questioning the application of this section to others besides former Confederates, though, I should note that this verdict was not overturned due to perceived “improprieties” in barring others besides former Confederates for treason under this clause. Rather, it was overturned because of the perceived “improper actions” of one of the judges in this case – namely, Justice Kenesaw Mountain Landis. Thus, this section is still in force against people who commit treason even today, and is not just a “historical” clause about a group of offenders that have long since died.

Victor L. Berger, a Socialist who was barred under this clause in 1919 and 1920

Section 4: South not to be compensated for pro-Confederate war debts, or for the “loss or emancipation of any slave”

A prior amendment had stated that “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.” (Source: Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, ratified 1865) With this in mind, the Fourteenth Amendment added that “The validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law, including debts incurred for payment of pensions and bounties for services in suppressing insurrection and rebellion, shall not be questioned. But neither the United States nor any State shall assume or pay any debt or obligation incurred in aid of insurrection or rebellion against the United States, or any claim for the loss or emancipation of any slave; but all such debts, obligations, and claims shall be held illegal and void.” (Source: Section 4 of the amendment) Thus, the amendment clarified that slave-owners were not to be compensated for the “loss or emancipation of any slave.” It also clarified that Southerners could not be compensated for pro-Confederate war debts, although Northerners could be compensated for pro-Union war debts.

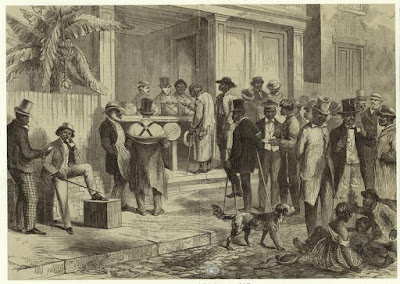

Freedmen voting in New Orleans, 1867 (during the Reconstruction Era)

Section 5: The Congress shall have power to “enforce” the provisions of this article

Finally, the Fourteenth Amendment said that “The Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.” (Source: Section 5 of the amendment) This is the section that gave teeth to the rest of the amendment. Without this section, virtually no other part of the Fourteenth Amendment (if any) could actually have been enforced.

Footnote to this blog post:

This blog post has been spliced together from bits and pieces of some of my other blog posts. As you may have noticed, the Fourteenth Amendment covers several topics, and was thus relevant to several areas of my blog series about the Constitution (which I link to here).

If you liked this post, you might also like:

Actually, the death penalty is constitutional (as the Fifth Amendment makes clear)

The complicated legacy of the “Three-Fifths Clause”

Some parts of the Constitution mention “Indians” and “Indian tribes” …

The Constitution keeps our elected officials on a short leash

A review of PBS's “The Abolitionists”

A review of Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln” (about the Thirteenth Amendment)

A review of PBS’s “Reconstruction: The Second Civil War”

Who can vote in the United States?: The voting rights amendments

No comments:

Post a Comment