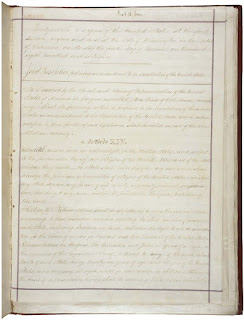

"A person charged in any state with treason, felony, or other crime, who shall flee justice, and be found in another state, shall, on demand of the executive authority of the state from which he fled, be delivered up, to be removed to the state having jurisdiction of the crime."

- Article 4, Section 2, Paragraph 2 of the Constitution

Headquarters of the United States Department of Justice, or "DOJ"

Although the president enforces the laws, they can't punish people without the courts ...

In our

Constitution, it says that the president "

shall take care that the laws be faithfully executed, and shall commission all the officers of the United States" (Source:

Article 2, Section 3). This includes prosecutors and police officers. Many of these laws to be "faithfully executed" authorize particular

punishments for various actions, from fines to imprisonment to being

executed (depending on the seriousness of the offense, as perceived by the

Congress). If the president had

carte blanche to enforce these laws passed by Congress, with no limits to this power, he could carry out these punishments anytime that he said these laws were violated -

or even at times when they were not. (If, that is, there were no judicial branch to check this power, and require him to prove that these violations actually happened as he claimed they did.) Thus the Constitution created a

judicial branch that was as independent as possible from the

President and the

Congress, so that no one group would possess the power to enforce these laws at their own whim or fancy. This is one of the real bulwarks of our

Constitution, and is one of the true guarantees of our liberties. Thus, I wish to spend some time on it in this post, and educate us all about our

constitutional rights as American citizens - particularly those found in the

Bill of Rights.

Supreme Court of the United States

... so the very existence of the court system is itself a check on the presidency

Specifically, the Constitution said that "The judicial power of the United States,

shall be vested in one supreme court, and in such inferior courts as the Congress may, from time to time, ordain and establish. The judges, both of the supreme and inferior courts, shall hold their offices during good behaviour, and shall, at stated times, receive for their services a compensation, which shall not be diminished during their continuance in office." (Source:

Article 3, Section 1) The

courts have a certain power to strike down laws passed by the Congress, which is another important power that I should note (at least in passing) before moving on to my main topic, which is judicial restraints on the president and the police force. (I discuss striking down laws in some detail in

one of my other blog posts, if you're interested in that subject. This post, by contrast, will be more focused on the

Bill of Rights, and on the judicial checks on the executive branch.)

U. S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals (an influential appeals court) - Pasadena, California