Deciphering the Maya glyphs opened up an entire world to historians …

Deciphering the Maya glyphs opened up an entire world to historians. People had long known about Ancient Maya civilization, and it was famous for the monuments that it had left behind. But until recent times, the inscriptions on these monuments had long proved impossible for linguists to decipher. The breaking of the Maya code was one of the greatest accomplishments in the history of linguistics, and allowed scholars to learn much about the early history of the Americas. It opened up a world for future study, and allowed the modern Maya people to have a greater connection with their ancestors and their heritage. Europeans are known for their colonial empires, which did not always treat the native peoples kindly (to put it mildly). Indeed, the Spanish Conquistadors had done their best to destroy many of the written Maya records that were available in their own time. But the European and North American scholars who deciphered Ancient Maya are a prominent exception to this. They did the surviving Maya an invaluable favor, by helping to undo some of the cultural damage caused by the Conquistadors.

Sadly, much of the evidence was destroyed by the Conquistadors via book-burning

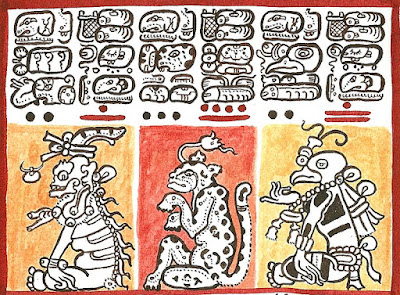

PBS did a great documentary about this, called “Breaking the Maya Code.” In two hours of runtime, it helped to chronicle this great accomplishment. This program starts with the Spanish Conquest, which (again) destroyed much of the evidence through book-burning, with the confiscation of the doomed books being enforced at unfortunate gunpoint. But thankfully, some of the evidence survived this violent (and tragic) episode. Some of it was later found way across the ocean in Europe, far away from Mesoamerica. These records give some valuable samples of Maya writing, which proved the key to its eventual decipherment. But scholars were already running into serious problems from the sheer complexity of the writing system. It had a massive number of symbols, somewhat like the number found in Japanese or Chinese. And the system seemed to European scholars to be visual chaos, with many symbols tucked inside of other symbols. Cracking a code of this kind would not be easy.

A few pages of the Dresden Codex

Looking for clues in how the sounds of Modern Maya were pronounced

It was not until the nineteenth and twentieth centuries that scholars made any serious attempts to decipher the ancient glyphs. Some of them tried to learn Modern Maya, and looked for clues in how the language was pronounced. Their initial theories seemed to be debunked, when Ancient Maya glyphs for words like “dog” seemed to be pronounced differently than a Modern Maya speaker would expect. They figured that the language had changed too much since Spanish colonization, and some despaired of ever overcoming these difficulties. But, in fact, the Maya had multiple words for “dog,” and one of these words did match the latest theories from the linguists. Thus, these scholars may have been premature in their jettisoning of these theories. They were right to look for clues in the sounds of spoken Maya, even though the language had indeed changed since the Spanish Conquest. This provided linguists with some valuable oral data, to compare with the written data from the glyphs.

Yucatec Maya writing in the Dresden Codex

The discovery that the Maya monuments were about glorifying their kings

Others tried to decipher the language, but the politics of the twentieth century had a way of obscuring things. Soviet scholars did some innovative work on the subject, which Soviet propagandists did their best to trumpet for the world. They argued that the linguists were using an innovative “Marxist-Leninist” approach to decipherment, which was a little exaggerated. As this documentary notes, many Western scholars were thus dismissive of the new findings – although, in fairness, people had reason to be suspicious of the Soviet propaganda. The Soviets had a track record of lying about many things, and it wasn’t much of a stretch to add “scholarly accomplishments” to the ever-expanding list of Soviet spin-jobs. But despite the track record of their government (and the Soviet system more generally), the Soviet scholars themselves had some real contributions to make, which eventually received the attention from Westerners that they deserved. On other academic fronts, scholars were starting to realize the general content of many of the Maya glyphs. As with many cultures around the world, the Maya writing glorified the accomplishments of their kings, and recorded political history in great detail. It seems safe to say that, like the rulers of every culture, the Maya kings did their best to spin their record to their own advantage. As with political writings from any other culture, some of it has to be taken with a grain of salt. But discovering the political content of these glyphs proved a major breakthrough in any case, even though it was still hard to actually read the ancient script.

Maya glyphs in stucco at the Museo de sitio in Palenque, Mexico

The pace of progress was later accelerated by Xerox technology and fax machines

In the later twentieth century, technological developments began to accelerate the pace of progress. This is mainly due to Xerox technology, and some of the early fax machines. (Remember, this is the later twentieth century.) Specifically, these allowed actual photographs of the glyphs to be easily distributed and disseminated to other scholars in the field. It’s hard to decipher a script when you don’t have actual pictures of the writing itself. But now, many scholars did have access to these pictures. Thus, scholars were finally able to read the long-forgotten language of the Maya writings. Scholars can now read 90 percent of the Maya glyphs with reasonable accuracy, which is an amazing achievement. As stated earlier, this gave the Modern Maya some unprecedented access to their own heritage, and is one of the greatest accomplishments in the history of linguistic science to boot. It is up there with the decipherment of the Rosetta Stone, or the decipherment of the “Linear B” script once used to write the Greek language – before the Greek alphabet had even been invented.

Detail of the Dresden Codex (modern reproduction)

This program is good at visually showing some of the complexities of Maya writing

This program is excellent at visually showing some of the complexities of Maya writing. And whatever the difficulties of efficient writing in that system, its aesthetic value is clear and undeniable. It was cool to see so many samples of Maya writing in this program, and hear a basic version of the complicated linguistic mechanics that were operating behind the scenes. Obviously, one can’t learn the Maya language in a two-hour film, so some things have to be watered down to make them more accessible to the masses in a brief program. But you get a sense of just how complicated it was to crack this code, and some viewers may well be inspired to learn more about the subject. I have some basic background in linguistics, but I doubt that I would ever be able to do innovative work in decipherment. I have enough trouble learning Biblical Hebrew and Greek from textbooks, which spell out most of the grammatical features for the benefit of the uninitiated. I didn’t have to fight as hard for every detail of the languages – and, in all honesty, their writing systems are far more intuitive than the Maya glyphs. I believe that the people who deciphered these glyphs have abilities far beyond my own, and I have deep respect for the people who did it.

Maya glyphs at National Museum of Anthropology (Mexico)

Conclusion: Great storytelling about the discovery of a proud (and very ancient) history

There are many writing systems which have still not been deciphered, so there are plenty of opportunities for young scholars to make their mark – in this generation, or in a far distant one. Their work will likely be unknown to many, but scholars of future generations may know their names, and be familiar with their work. This program may inspire some bright young students to enter the field, and further expand the boundaries of linguistic (and other) science. And it’s great storytelling to boot, which helps to brings to life the discovery of a proud (and very ancient) history.

If you liked this post, you might also like:

No comments:

Post a Comment