“Representing the will of the people of the entire nation, it has formulated the organization law for the Central People's Government of the People's Republic of China, elected Mao Tse-tung as chairman of the Central People's Government … [hence follow the names of the vice chairmen and the committee members] … to form the Central People's Government Committee, declared the founding of the People's Republic of China, and decided on Peking as the national capital.”

– Proclamation of the Central People's Government of the People's Republic of China, 1 October 1949

I had seen a number of Michael Wood films before seeing this series, including “The Story of India” and (The) “Story of England.” I had enjoyed these two films greatly, but I think that I may have enjoyed “The Story of China” even more than these other two epic histories. This series has more of a unified narrative than “The Story of India” does, and doesn't seem as much like a collection of random anecdotes about its subject. Although it is not a political history, the cultural history that it focuses on is woven together into a fascinating narrative, and has the effect of teaching the viewer much about China.

China gave birth to two major religions (which were Taoism and Confucianism) …

Of the different episodes, my personal favorites may have been those dealing with the Ancient Chinese. These give much insight into the classical civilization of the area, including the arrival of the three major religions that are still practiced there today. The oldest such religion is probably Taoism (also spelled Daoism), a native Chinese religion which is traditionally said to have come from the philosopher Laozi (also spelled Lao Tzu). The most famous of the Taoist scriptures may be the Tao te Ching, which was probably written some centuries before Jesus Christ. It has also had some influence in the West today. Many Asian religions arguably have no equivalent of the Western “Thou shalt have no other gods before me,” and so their adherents will often identify themselves with multiple Asian religions. This is, in fact, the norm in contemporary Asian culture. Thus, many Taoists today are also Confucianists, or followers of the Chinese philosopher called “Kong-fuzi” (or “Confucius”). “Confucius” was another thinker who actually wrote some centuries before Jesus Christ. Of all of the major Eastern philosophers, he is probably the most famous in the West today. Unfortunately, Confucianism was openly persecuted by the communists, under the later rule of Mao Zedong. Mao's “culture war” against the traditional Chinese heritage was a crime in and of itself, with Confucianism among his most prominent targets. (More about that “culture war” later on in this post. For now, I will stick to discussing the Ancient Chinese culture.)

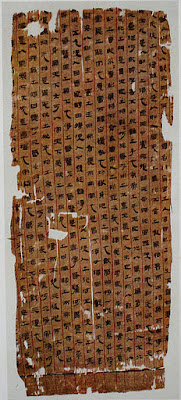

Taoist manuscript of the Tao te Ching, one of the Taoist scriptures

… but also imported a third one (Buddhism) from the outside – namely, from India …

Many East Asians today (including Japanese and Koreans) actually view the Ancient Chinese in the same way that the Europeans view the Ancient Greeks and Romans – as a “classical civilization” that was a fountain of high culture. I should note that Taoism and Confucianism are both native Chinese religions, and are thus among Ancient China's most influential legacies today. But there is still another religion with a major influence on Chinese life, which is Buddhism. Unlike Taoism and Confucianism, though, Buddhism was actually imported from the outside (namely, from India). Thus, it is probably India's greatest export to China (and many other nations as well). The consensus among scholars today is that various missionaries from India probably brought their religion to nearby China, but there is still some debate about whether it entered via a maritime route, or via an overland route such as the Silk Road. From its new base in China, Buddhism was then exported further to other nearby nations (such as Japan), but its largest population is still in China, where it is often mixed with the native religions of Taoism and Confucianism. (For whatever reason, Buddhism never really caught on in its birthplace of India, and still has its greatest presence in Eastern Asia.)

Map of the People's Republic of China today

Minority populations of Christians and Muslims, and Chinese policies on religious freedom

China also has some minority populations of Christians and Muslims today, whose religions were both imported from the outside. In prior times, European missionaries had tried to spread the Christian religion there, and colonizing European powers had once tried to force it on the people of China. Thus, Christianity has a somewhat controversial history in China, which may be part of the reason that Christian missionaries are not allowed there today. Of course, China also has a well-known policy of state atheism today, which may contribute further to their hostility to outside religious influence. Fortunately, they are now more tolerant of religious freedom than they were under Mao Zedong, and they no longer make war against the Confucian religion as Mao Zedong once did. (At the time that I write this, their current government views Confucianism as “promoting social harmony,” and would not see it as “hostile” to their own communist society. This is as it should be.)

Tomb of Confucius in Kong Lin cemetery, Qufu, Shandong Province

Some of the diverse topics covered in this series, including free trade and relations with Europe

This documentary also covers the past Chinese experience with economic freedom, and how they were active in using ships for free trade. At this time, these ships were often more advanced than their equivalents in the West, and had a great influence on European nautical technology as a result. There is also much discussion of the Chinese concept of the “Mandate of Heaven,” and its effect on their history. There is also an episode on the Ming dynasty, which is among the best remembered dynasties, although it was one of the more oppressive regimes in Chinese history. The Qing dynasty (pronounced “Ching”) is sometimes known as “the last empire,” and there is an episode on them as well. There is also some discussion of the Portuguese colonization of Macau in 1557, and the British colonization of Hong Kong in 1841 – with the related Opium War between Britain and China from 1839 to 1842. Indeed, this prior British experience with China may have been part of the reason that the BBC wanted to make this documentary to begin with. The British actually have much experience with China, and do not feel uniformly proud of all of it (to put it mildly). Their past experience with China has thus made them very interested in the region.

British ship destroying Chinese “war junks” in the First Opium War, 1841

Advances in astronomy, and the major invention of the printing press …

The period that I call the “Chinese Renaissance” is also discussed in some depth here, with some very respectable advances in astronomy (among other things). They also invented the printing press, which would later be used extensively by the Europeans. But this technology never really caught on in China itself, perhaps because the Chinese writing system has more than 1,000 characters – quite a few more than that, actually. This is obviously too many characters to use in a typical printing press, although computer software has since made it much easier to print their writing system. This is because the Chinese today use a modified Roman alphabet to input their writing system into computers, and a computer software program shows the popular Chinese characters that are associated with those Roman spellings. They just have to choose the particular character that they want to use, which makes it much easier to computerize their writing system in this way. Interestingly, they were also thinking about using the Cyrillic alphabet to fulfill this function, since that was the system used by their nearby neighbor of Russia. But because the Roman system was used by nearby Asian neighbors (like Japan) to input their languages into computers, the Chinese instead chose to use the Roman alphabet for this purpose. This was probably a wise choice, and they would seem to be reaping the benefits of it today.

Chinese characters translating to “Mandarin Chinese”

Fortunately, this program does not gloss over the crimes of Mao Zedong …

Regarding the twentieth century, I was afraid that Mr. Wood would try to gloss over Mao Zedong, since this is fashionable among some liberals today. For example, Obama's former communications adviser Anita Dunn – who is now a senior adviser to President Biden – once referred to Mao Zedong as one of her “favorite political philosophers” (source: video record of her comment). Surprisingly, though, Michael Wood presents Mao's crimes quite candidly; and rightly argues that he made war against the traditional Chinese heritage, such as Confucianism (a crime in and of itself, as I mentioned earlier). It's true that he doesn't mention the revenge killings following the Chinese Civil War, or the even worse death toll under the so-called “land reforms” – in which a certain class of landowner was targeted for extermination. It's also true that he doesn't mention how many people died under the so-called “Cultural Revolution,” although he does briefly mention the “Cultural Revolution” – and, thankfully, he portrays it negatively there. But he does cover the so-called “Great Leap Forward” in some depth, and gives the figure of 30 million as the number who died under the Great Chinese Famine that followed it. Elsewhere on this blog, I offered the more conservative estimate of 18 million deaths; because conservative estimates are easier to defend, when one's purpose is to criticize Maoism. Nonetheless, I suspect that the larger number advanced by Michael Wood may be closer to the ghastly truth of the matter; and even the conservative estimate of 18 million deaths exceeds the death toll of the European Holocaust. Thus, I am glad that Michael Wood didn't try to defend Mao Zedong, or his legacy of mass murder. But on a happier note, I am glad that he mentioned the positive effects of the Nixon visit to China. (But that's a subject for another post.)

Mao Zedong, also spelled “Mao Tse-tung” (dictator of communist China at that time)

Conclusion: The best television history of China that you're likely to find

In his closing remarks, Michael Wood argues that in China's search for a more “democratic socialist” society, the rest of the world should wish it well. While I don't agree with the part about being “democratic socialist,” I actually agree with the overall tenor of “wish[ing] them well,” and would just measure this progress differently than he does. China may be a capitalist society in some senses of that word today, even if true free markets are not yet to be found there (although it may yet open up further to the outside world in the future). One can always hope that the Chinese people will abandon every Marxist vestige of their former governments, and instead look for happiness in the ancient values of their heritage and history – the ones that Mao Zedong tried to suppress, in his barbaric war against traditional Chinese culture. I would tend to agree with Michael Wood that China has already made some excellent progress in this matter, that a prosperous and peaceful China (whenever encountered) will always be of benefit to the free world, and that a memory of their past will be the key to their future.

Footnote to this blog post:

With regards to the twentieth century, I should also note that Michael Wood likewise didn't mention the three international incidents over Taiwan, the transfer of Hong Kong in 1997, or the transfer of Macau in 1999. But in an episode like this, some things inevitably have to be cut out; so I won't criticize him too much for this.

For more about these aspects of twentieth-century Chinese history, see this other blog post of mine.

DVD at Amazon

Disclosure: I am an Amazon affiliate marketer, and can sometimes make money when you buy the product using the link(s) above.

If you liked this post, you might also like:

A review of Michael Wood's “Story of England”

A review of Michael Wood's “The Story of India”

A review of David Grubin's “The Buddha: The Story of Siddhartha”

A review of “Japan: Memoirs of a Secret Empire” (PBS Empires)

Forgotten battlegrounds of the World Wars: Asia and the Pacific

Why Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan didn't go communist (when the rest of China did)

Nixon's visit to China: Driving a wedge between China and the Soviet Union

No comments:

Post a Comment