“If God spare my life, ere many years I will cause a boy that driveth the plough, shall know more of the Scripture than thou dost!”

– William Tyndale (author of an early translation of the Bible into English), in a heated exchange with a priest

What led up to the King James Version of the Bible (first published in 1611)?

Even today, the King James Version of the Bible is the most commonly-used Biblical translation in the United States. Its influence is declining in some other English-speaking countries, but its status still remains strong today in many others. Even among atheists like Richard Dawkins, it is acknowledged as “a great work of literature.” Dawkins also added that “A native speaker of English who has never read a word of the King James Bible is verging on the barbarian.” Certainly the KJV (as it is often abbreviated) has had a great influence upon the history of the English language. One would have to turn to Shakespeare to find comparable influence upon the history of our own language. I would like to pay a brief tribute to the unsung heroes who helped to bring us this translation into English, as well as those who brought us other translations into other languages. But my focus here will be on the history involved, and what led to the writing of the King James Bible.

St. Jerome, mentioned below

There was the Latin translation of the Bible, translated by John Wycliffe into English

Our story begins in the fourth century AD. Earlier in that century, the Roman emperor Constantine had converted to Christianity, eventually converting most of the Roman Empire along with him. Later in that century, a priest named Jerome would help to translate the Bible into his native Latin. Most of the Catholic Church’s Vulgate Bible comes from this man, now known as “St. Jerome.” At the time, translating the Bible into Latin was intended to make the book available to a wider audience, since Latin was still used as a native language at this time. But this translation continued to be used long after Latin had ceased to be a native language. It was this Vulgate translation that was later printed as the famous “Gutenberg Bible,” when the printing press was still quite new. I honor St. Jerome for his efforts to expand the Bible’s audience, and I honor those who have studied Latin to read this Vulgate Bible. But there were some in the church who wanted to deny others access to the Biblical text. This is why some of them forbade translating the Bible into any other language. There was notable dissent from some Catholics, such as the priest John Wycliffe. Late in the Middle Ages (specifically, the fourteenth century), Mr. Wycliffe and his followers helped to translate the Bible from that Latin text into English. The English would today be called “Middle English,” but this was the time in which that stage of the language was actually spoken as a modern language. Thus, I honor John Wycliffe for his efforts in this regard.

Gutenberg Bible

John Wycliffe

Martin Luther’s German Bible, William Tyndale, and Henry the Eighth’s Great Bible

But some thought that the Bible should be translated from the original text in Hebrew and Greek, rather than from Jerome’s translation into Latin. Thus, during the Renaissance period, Martin Luther and his associates helped to translate the Bible into German. Soon after that, his contemporary William Tyndale helped to translate the Bible into English – again, from the original Hebrew and Greek text. Tyndale had a poet’s touch, and the King James Version borrowed heavily from his work. But Tyndale would pay a price for this translation with his life. He was among a number of people who sacrificed their lives to bring us the Bible “in the vernacular” – that is, in languages that people can actually understand and read. Tyndale prayed: “Lord! Open the King of England’s eyes.” The king to which he referred was the transformative Henry the Eighth, who had already formed his own church. (Specifically, the Church of England.) In fact, the king was already married to Anne Boleyn, the woman who had motivated both his infamous divorce and his conversion to Protestantism. Henry the Eighth had even commissioned the Great Bible, the first authorized translation of the Bible into English, in 1533. (Tyndale died in 1536.) But the Great Bible’s completed version was not finished until 1539, three years after the death of Tyndale. Thus, William Tyndale had not seen his work fully realized when he was executed by strangulation in 1536.

William Tyndale

Queen Elizabeth’s “Bishops’ Bible,” the Geneva Bible, and finally the King James Version

One of Henry’s daughters was Queen Elizabeth the First, the product of his marriage to Anne Boleyn. Elizabeth commissioned the Bishops’ Bible during her reign, an updated version of the Great Bible. This was the second authorized translation of the Bible into English. But the King James Version of the Bible also bears some of the influence of the not-so-authorized Geneva Bible. This is another historically significant English version of the Bible. Later on, Queen Elizabeth the First was succeeded by “King James” – the man after whom the “King James Version of the Bible” is named. He had been “James the Sixth” of Scotland, but he now became James the First of England. In the seventeenth century, he commissioned the third authorized translation of the Bible into English. This is the one that still bears his name. I have not read the Apocryphal parts of this Bible, but I have read everything else in both its Old and New Testaments. Thus, I have grown to admire the quality of its language.

James the Sixth of Scotland, and James the First of England – a.k.a. “King James”

The debt that we owe to those who brought us the Bible, in languages that we can understand

As D. Todd Christofferson once put it, “William Tyndale was not the first, nor the last, of those who in many countries and languages have sacrificed, even to the point of death, to bring the word of God out of obscurity. We owe them all a great debt of gratitude.” (Source: “The Blessing of Scripture,” 2010) I fully agree with all of this. I feel that we owe a great debt of gratitude to those who brought us the Bible in our own languages. I still believe that there is value in reading the original Hebrew and Greek, which is why I’m now learning these languages for myself. But many can’t (or won’t) learn these languages, because they have competing priorities like jobs and families – priorities which are obviously very necessary and important. Thus, I see the availability of translations as a necessity. The Bible needs to be accessible, if it is to enjoy the influence that it so deserves. You can find many such translations today, including the New International Version and the New Revised Version in English. Each of them has a sizable share of the English-speaking Bible readership. But the King James Version still has a sizable following in this readership, particularly in the United States. And many of those who prefer more modern English would acknowledge – readily acknowledge – the historical importance of the King James Version, and its effect upon the history of the English language. Some would even see it as a step in the right direction, even if it’s not the version that they would choose to use themselves.

The title page to the 1611 first edition

I don’t care what version you read, but I love the King James Version of the Bible!

So let me end with a disclaimer: My intention here is not to enter into debates about which translation is the most faithful to the original text. Nor is it to debate the merits of Elizabethan English versus more contemporary English versions. Translation seems to be more of an art than a science, and it is to be expected that aesthetic tastes will differ somewhat from person to person. But for my own part, I admire the elegant language of the King James Version. To me, it is rather poetic and beautiful. I freely admit that I am rather uninformed about literary matters, and would readily acknowledge my lack of sophistication in these things. But I have a right to an opinion as much as anyone else does, particularly when that opinion has come from actually reading the King James Version of the Bible.

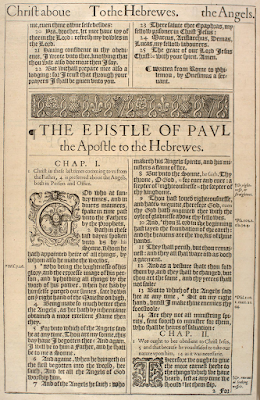

The opening of the Epistle to the Hebrews of the 1611 edition of the Authorized Version

Invitation to read any version of the Bible for yourself, in any language that you choose

Whatever version you prefer, I would invite everyone to read the Bible for themselves, in any language that they choose – whether they are of faith or not. Some have sacrificed much to make the text available to us. Some have even sacrificed all. To me, the best tribute of gratitude that we can pay them is to accept their gift, and read the Holy Bible for ourselves. Then, perhaps, their sacrifice will continue to have meaning. Then, perhaps, their gift will keep on giving, to the current generation … and beyond.

The full text of the King James Version is available here.

If you liked this post, you might also like:

No comments:

Post a Comment